Mashing ‘Pictures at an Exhibition’ Into an RPG

This piece evokes fantastic imagery that includes deformed Gnomes, ruined castles, ancient catacombs, and terrifying witches.

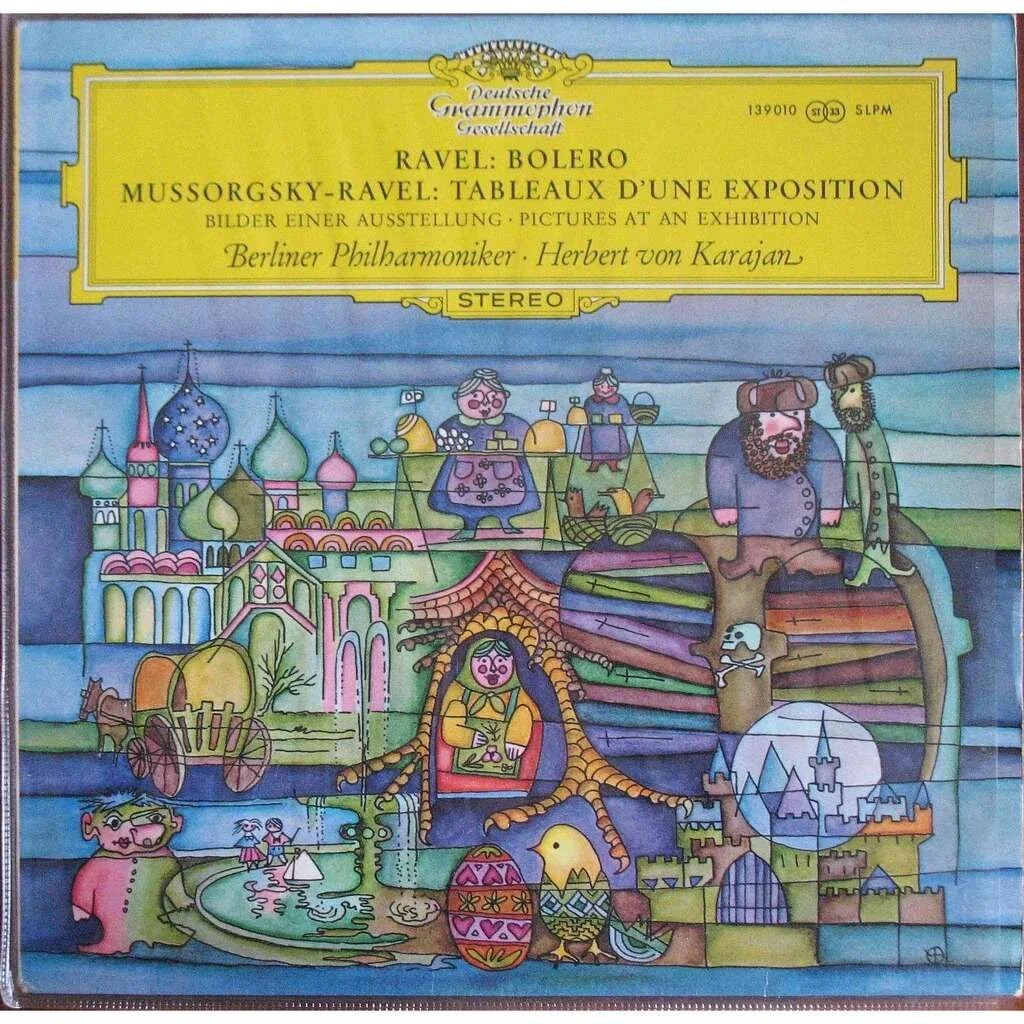

One of the very first pieces of music I can ever remember hearing, and the first I ever fell in love with, is “Pictures at an Exhibition,” a suite of 10 movements — what we would today call an “album with 10 songs” — created in 1874 by Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky. It is replete with fantastic imagery that includes deformed Gnomes, ruined castles, bustling marketplaces, the catacombs of Paris, ancient and terrifying witches, and ceremonial gateways to great cities. I have, in fact, long contemplated how I might create a game scenario based on it, and our "d-Infinity Live! Amusical Proposition Challenge" has prompted me to take my thoughts on this to the next step.

My proposed creation is thus a campaign-length adventure consisting of 10 scenarios, each based on one of the movements of “Pictures at an Exhibition.” While I initially envisioned this as a fantasy adventure, Mussorgksy was musically composing scenes which, in most cases, were set in what for him was the modern era, and I would more likely follow his lead and set this primarily in the 1870s and square in the middle of the Victorian Era. And, the more I have thought about it, the more I think this scenario would adapt well to scenario set in our own modern era that involves international intrigue, gang warfare, a secret genetics lab, and an ominous virtual world based on the darkest of Russian fairy tales.

So, for example, Mussorgy’s movement No. 3 of “Pictures at an Exhibition” is titled “Tuileries” and is meant to evoke the idea of children in the Tuileries Garden of Paris arguing over a game. When one listens to the heavy metal version of this movement by German hard rock band Mekong Delta, however, it is far easier to envision a couple of young thugs arguing over a backgammon game gone bad and violence erupting when the one who appears to have lost refuses to make good on his bet. Some of electronic instrumentals are even evocative of automatic weapon fire, which is not something that will be suggested most people by the original 19th century version.

Similar expansions of genre are suggested by other adaptations from portions of “Pictures at an Exhibition,” such as metal band Armored Saint’s use of Mussorgsky’s movement No. 10, “Great Gate of Kiev,” as the basis for its song “March of the Saint.”

First, the various movements of the suite are scattered throughout Europe, including locations in Russia, Ukraine, France, and Italy, so the need to travel from place-to-place either needs to be addressed or explicitly ignored. If the campaign takes places partially or wholly during the Victorian Age, are characters traveling by train, mail coach, ship, or a combination of all those? If it is in the modern era, do any of the characters have backgrounds that might cause them to be on international watchlists or nationalities that might draw undue attention to them in certain countries? Does their inclination to carry firearms or other specialized equipment — which certainly will be the norm among player characters — impede their ability to fly commercially or to cross national borders?

Second, a number of Mussorgsky’s movements in "Pictures at an Exhibition" suggest a mythical setting outside of his 19th century reality, a Russian fairytale land inhabited by Gnomes and powerful witches. Creating a campaign-length scenario true to this vision would therefore require mechanics for traveling from one plane of reality to another — whether it be a magical world or a virtual one residing on a computer server deep beneath the streets of Paris — and for reinterpreting the skills of characters as necessary. A character who is a computer hacker in the modern era, for example, might be a sorcerer of sorts in the alternate reality.

Whatever the case, "Pictures at an Exhibition" invites develop into RPG material that mashes together not just different styles of music — as any number of artists have done with Mussorgsky's original work — as well as a mashup of genres and time periods, as him himself suggested in the approach he took to his magnum opus.