A Lot of Gall

As some modern medications become less useful over time, there’s been a push to open up medieval books and see if they knew something that we don’t.

In this column, I regularly spend a certain amount of time poking fun at our ancestors’ medical traditions. When you consider that less than a thousand years ago you had respected textbooks recommending that people collect and drink rainwater from a skull while performing ritualistic prayers under the mood – which is an actual remedy for surviving medieval British “leechbooks” – it’s easy to be a little bit contemptuous. This is, however, somewhat unfair. As more and more modern medications become less useful over time, particularly those antibiotics to which bacteria are rapidly becoming widely immune, there’s actually been a push in the established research centers to open up those ancient books and see if maybe, just maybe, they knew something that we don’t. As it turns out, there’s been some early evidence that some of their antibiotic treatments may be more effective than ours, and not less.

Still, to my knowledge, no research center in the world, respected or otherwise, is testing the rainwater-out-of-a-skull thing. I would dearly love to be the one to write an ethics proposal for that randomized control trial.

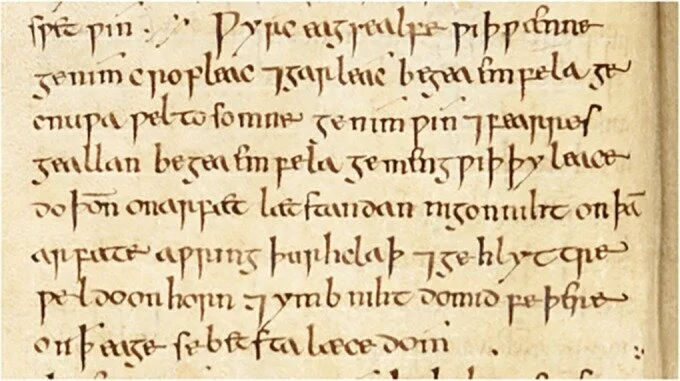

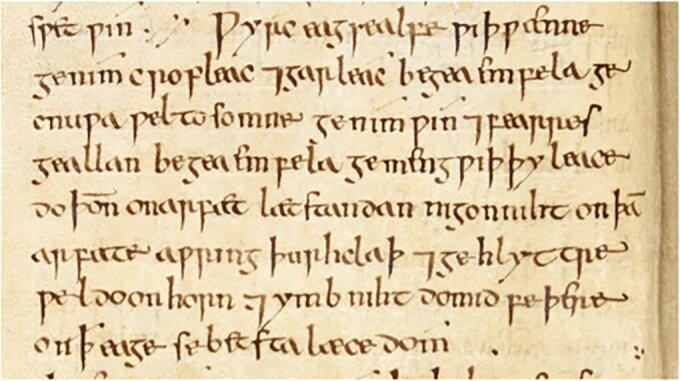

An article came out earlier this year which selected one plausible-seeming remedy and tested it, not merely in the setting of actual infection, but in the setting of antibiotic-resistant infection, which is something we’re really not very good at treating in modern hospitals. The remedy in question comes from Bald’s Leechbook, just one of the leechbooks which survive at least somewhat intact into the modern era. It’s thought to date to around the tenth century and, like most such books, is a curious combination of astute pharmacology intermixed with descriptions of the prayers best suited to ward off possession by an elf or warlock. This particular article looks at the “leechdom” or treatment for a particular form of eye infection. As transcribed in the article, here’s the Olde English and modern English recipe.

|

Ƿyrc eaȝsealf ƿiþ ƿænne: ȝenim cropleac; ȝarleac beȝea emfela, ȝecnuƿe ƿel tosomne, ȝenim ƿin; fearres ȝeallen beȝean emfela ȝemenȝ ƿiþ þy leaces, do þonne on arfæt læt standan niȝon niht on þæm arfæt aƿrinȝ þurh claþ, hlyttre ƿel, do on horn; ymb niht do mid feþre on eaȝe; se betsta læcedom. |

|

Make an eyesalve against a wen: take equal amounts of cropleac and garlic, pound well together, take equal amounts of wine and oxgall, mix with the alliums, put this in a brass vessel, let stand for nine nights in the brass vessel, wring through a cloth and clarify well, put in a horn and at night apply to the eye with a feather; the best medicine. |

Let’s break that down a bit; it’s always good to know understand what ingredients are called for because these are the things you’ll be sending player characters off to find. The recipe calls for two plants, garlic and a related species the exact translation of which is lost to us, which must be mixed with equal parts wine and (and this is the good part) the bile of an ox. Personally, I can hardly imagine someone who would be so sick that they would accept to drink such a concoction, but on the other hand I’ve seen people do some astonishingly extreme things when sick.

On a more pragmatic level, the recipe does contain ingredients which have the potential to be antibiotic. The interesting part is that they’re combined. In modern medicine, drugs tend to be given as pure as possible, and as isolated as possible, and the vast majority of the antibiotics you might take in your life won’t be mixed with another antibiotic unless you’re very, very sick. There are some important exceptions; it’s very common to give the antibiotic amoxicillin along with another drug called clavulanic acid, for example, because the clavulanic acid allows the amoxicillin to bypass the mechanism by which most bacteria are resistant to it. Still, by and large, we don’t use combinations like that. This recipe combines together several potential antibiotics. Garlic, onions, and other plants in the allium family can kill some bacteria. Bile also has some antibiotic effect; it’s thought to be part of how the gut protects itself from the bacteria you eat. Even the copper pot that the mixture has to be left in might help, because any copper molecules that leech into the mixture might kill bacteria. When the authors tested the recipe, it was able to kill bacteria both in a dish and in animal tissue; it wasn’t tested on actual sick humans. When any particular ingredient was removed it wasn’t effective (except for the copper, which doesn’t seem to have played a major role); something about the combination greatly enhanced the effect.

To summarize, the ancient healers who wrote these recipes knew that you could make a viable and effective medicine by combining several very weak medicines. Gaining this knowledge probably took decades, perhaps centuries of trial and error in which we can only imagine how many patients were undertreated or inadvertently poisoned, but they did have an effective remedy. A remedy which many people would have totally refused to drink, or been able to keep down if they did, but effective none the less.

A recipe like this provides a storyteller with an obvious quest idea which can easily be given to a group of players. A prominent individual is sick, and for one reason or another magical healing can’t be used (is the disease resistant to magic? Is the victim rapidly anti-magic for religious reasons?), and the PCs have to urgently track down the ingredients. It probably isn’t hard to access garlic and onion, and they probably have wine in their bags of holding anyway, but it might be a bit harder to find an ox they can slaughter for its gallbladder. Such a quest can easily be made more complicated, as well. Is oxgall too easy to obtain? Have the recipe call for dragongall instead. The story possibilities spin off endlessly.

More than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on August 29, 2015. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.