To Give And To Receive

The scariest thing about illness is, perhaps, that it spreads.

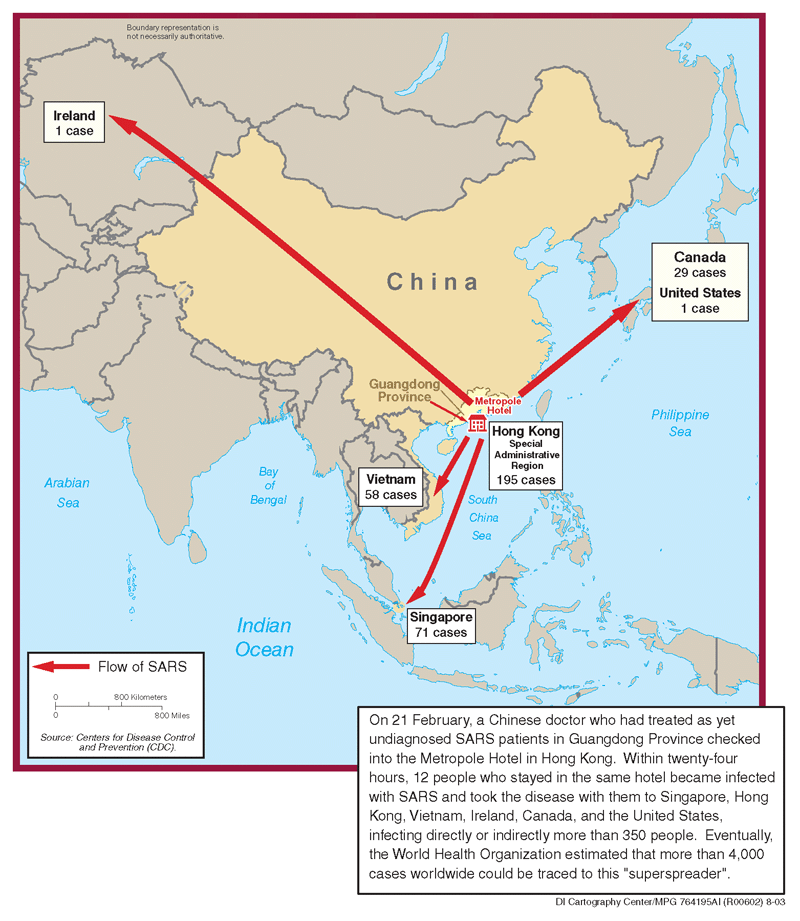

Actually, I don't really believe that's true. In my opinion, the scariest thing about illness is that there are so many sicknesses that can appear suddenly, with no warning, and destroy the life of someone who was, just one day before, happy, healthy, and functional. The SECOND scariest thing about illness, or at least infection, is probably is that it can spread. When someone close to you comes down with a cold, no matter how careful you are, there's a fair chance that you can get that cold. Fear of the Black Death put entire nations on lockdown in several periods throughout history. The HIV scare in the 80's frightened young people enough to cut down on them having sex, which not a lot of other forces can do. The SARS panic in the 2000's struck in time for it to feature prominently in my courses in medical school and redefined the way modern society approaches emergent diseases. When a storyteller wants to use sickness in a game, fear of illnesses is an essential story device, and this requires the storyteller to have an idea of how any given sickness spreads.

Consider the Black Death. There are a lot of things about the Black Death that neither historians nor scientists quite understand, one of which being, we aren't sure how it spread as quickly and as widely as it did. The best theories to date describe how fleas, on the bodies of rats, were carried along the Silk Road and across the seas by merchants and travelers. This explanation fails to explain quite a bit, but it's still the leading explanation, and what's key is that the plague was spread by the rapid evolution in human transit. Would the plague have spread as fast and as far in the era of triremes and camel-based caravans? Would there have been any area of the world that the plague didn't reach if those same merchants had teleportation magic?

Actually, that last question is one that we can approach answering. Obviously, we don't yet have functional teleportation technology here in the 21st century -- or if we do, it's not widely known about -- but we do have the modern air travel industry, which is continually evolving. Compared to traveling overland in the time of the Romans or crossing the Atlantic ocean in the time of galleons, modern air travel may as well be teleportation. Air travel (and teleportation) are fantastic ways for disease to travel for two reasons. First, they're unbelievably fast. Suppose a scribe contracts a deadly infection that takes one week to first show symptoms and become infectious. Your average human walks at between 3 and 6 kilometers per hour, not counting breaks or slowdowns because of climbing hills and such; a human who has walking speed near the upper-limit of average can walk from, say, Montreal, Canada, to New York, United States, a distance of roughly six hundred kilometers, in something in the area of one hundred hours, or four days... assuming he walks for 24 hours a day, which one has to assume would be a bit grueling for the average person. The same distance by car would take about six hours, not counting the time it takes to cross the US/Canada border, and by commercial flight you'd barely even have time to make a dent in your novel. Barring a few details, this is exactly what happened with the SARS pandemic; a highly infectious virus started off in one part of the world and was carried to the other side of the world by people who didn't know they were sick yet. In the case of SARS, there was the added complication of good old human nature; some people knew they were sick, but got onto their planes anyway because they placed their own convenience over the potential health of millions of people.

This month, a team working for the CDC published a study on tuberculosis in the United States (Woodruff et al. 2013. Predicting U.S. Tuberculosis Case Counts through 2020. PLoS ONE 8(6): e65276. This is a free-access article, so by all means, go read the original to learn more!). They examined ten years of infection data and used it to make inferences about what tuberculosis patterns might look like in the next decade. They made the important observation that "foreign-born persons accounted for 60% of all tuberculosis (TB) cases in the United States." This doesn't necessarily mean that all of this TB is being brought in by immigrants; it's important to remember that immigrant families are more likely to live in poorer-quality housing and in crowded conditions, and have poorer access to medical care, all of which increases their risk for infections in general and TB in particular. What they concluded was that the data suggests that fewer and fewer US-born individuals are being found to have TB, and they therefore predicted that we're going to see "a widening gap between the numbers of U.S.-born and foreign-born TB cases." The problem with this study is that some people are bound to use it as an argument against immigration from poorer countries, which is sort of missing the point. What it really underscores is that diseases which are rare in "civilized" lands can still be very common in other nations, and the more efficient world travel becomes, the easier it is for these diseases to spontaneously appear where they're least expected. The take-home message for storytellers is that there's no such thing as a disease that only afflicts other people when you can travel from India to England and back in a day, let alone cross dimensional boundaries and bring bacteria native to the Elemental Plane of Influenza back to the prime material.

Four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on June 22, 2013. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.