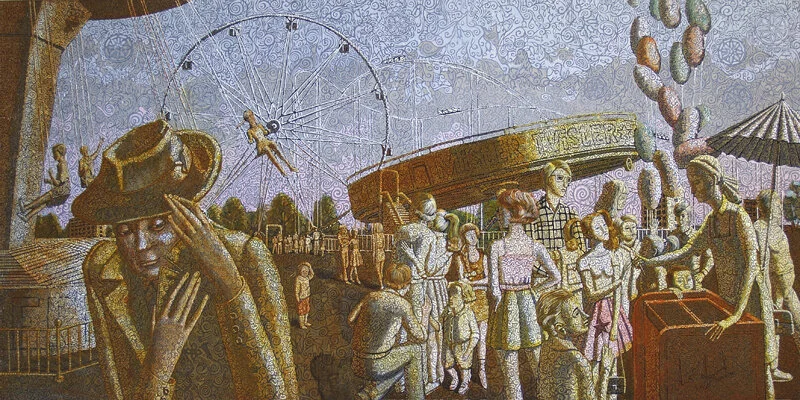

Deadly Amusements

Why is it that when there’s an amusement park in a game, it’s inevitably trying to kill you?

Dr. Eric Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC sourcebook, Insults & Injuries.

Why is it that when there’s an amusement park in a game, it’s inevitably trying to kill you?

As I write this, I’m taking a break from playing Fallout 4: Nuka-World, the latest expansion to the popular video game. In it, the protagonist finds himself in a defunct parody of Walt Disney World and, as should come as no surprise to anyone, many different groups try to destroy you. The one thing that Nuka-World does really well is showcase the wide variety of potentially deadly things one can find in an amusement park, including most of the classic clichés. For all the effort that the game’s writers and designers put into it, though, I was delighted to note that, if anything, they probably seriously underestimated just how dangerous an amusement park can be. Even ignoring the slow, lingering dangers that are easy not to think about – the unhealthy food and the serious hit they can do to one’s socioeconomic status – amusement parks by all rights ought to be incredibly dangerous places, and the fact that there are so few injuries and deaths each year is a testament to how far the science of engineering has come.

Of course, my job in writing this is to help the reader make things MORE dangerous, not less, so to stimulate your own imagination, here’s a breakdown of some of the most common causes of morbidity and morality from real-world parks, which are just begging to be exaggerated in the game of our choice.

Several studies have looked at data from emergency departments near amusement parks and compiled the different sort of injuries that happen there. The data is, for the most part, the exact opposite of terrifying; most people reading such data would be fundamentally unimpressed by the number and nature of injuries reported. By far the most common theme park-related injuries are lacerations – cuts, scrapes, and the like – followed by concussion and head trauma. The most common non-traumatic injury is consistently heat-related illness, such as heat-stroke and dehydration. Interestingly and importantly, only about one in four injuries is ever related to the actual park rides; the vast majority of injuries occur in people who fall while walking down the street, or walk into a lamp post, or fail to take basic case of themselves and occasionally have a sip of water, or otherwise get themselves hurt doing something a bit silly. Altogether, only about one in ten people injured in parks have to stay in hospital for at least one night and in most of the studies there were no fatalities. The bottom line of all of these studies has been that the vast majority of injuries sustained in amusement parks are totally benign and, from a certain point of view, laughable.

True story: I visited Walt Disney World about four years ago and I personally witnessed two people sustain potentially serious injuries. It happened before we were even through the park gates, when a middle-aged woman tripped and fell, inadvertently pulling over another middle-aged woman walking next to her. Both women hit their heads hard enough that it would have been reasonable to advise them to go to the ER. The park had nothing to do with it except for being the place they were walking towards. I feel as though this says something about life, but I honestly don’t know what.

When more serious injuries are seen, it’s more often in children, and more often at small regional fairs as opposed to major amusement parks, and even so, less than five percent of injured kids have to stay in hospital for any lengthy period of time. Such more serious injuries tend to consist of broken bones (arms much more commonly than legs), minor sprains, or shoulder dislocations (fun fact: according to some sources, the dislocations are MUCH more likely to be inflicted by an impatient parent than by a ride).

Of course, since such studies look at data from emergency departments, they probably wouldn’t include people who died on scene and never passed through an ER. They also probably under-estimate the number of real injuries, because some injuries get treated at the park and some people who get injured are too stubborn (or, especially in the US, can’t afford) to seek help.

On top of all that fairly obvious stuff, there’s a host of other illnesses that can be unexpectedly triggered by amusement park rides. Most of these injuries are linked to roller coasters and their rapid accelerations and decelerations. Sudden sharp head movements can detach the retina in the eyes, leading the vision loss, or tear major arteries in the neck or head, causing stroke. Injuries such as these are exceedingly rare, fortunately – rare enough that when they do happen, someone can publish an entire paper about it. According to one paper, between 1979 and 2000, there were a total of fourteen cases of people who suffered torn blood vessels from rollercoasters, which doesn’t sound like very much when you consider the literally millions of people who have ridden rollercoasters in those twenty years. Such one-in-a-million injuries aren’t the sort of thing that should leave any sensible person lying awake at night afraid to enter a park, but they do indicate to us ways that a place like West World might rack up a few extra bodies.

In summary, these studies show us one unavoidable fact: in real life, amusement parks have a lot of ways in which they ought to be able to hurt people, but because of good design, very few people are actually hurt, and most of the people who are hurt aren’t harmed because of something dangerous inherent to the actual park. From the perspective of a consumer, this is tremendously reassuring, but it leaves the storyteller a little bit disappointed.