Cure Light Scrooge

Illness in children is something that most people find particularly horrible.

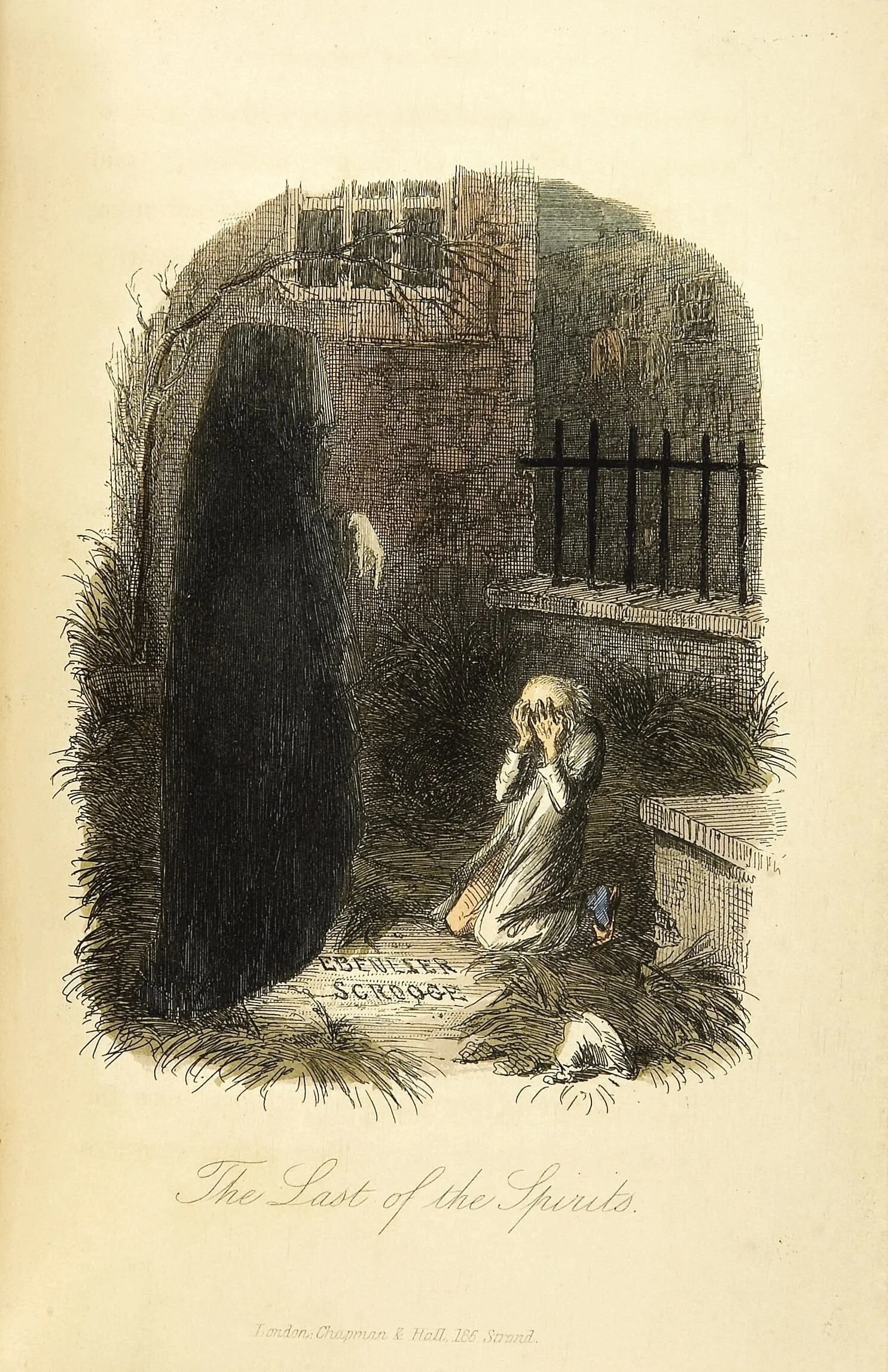

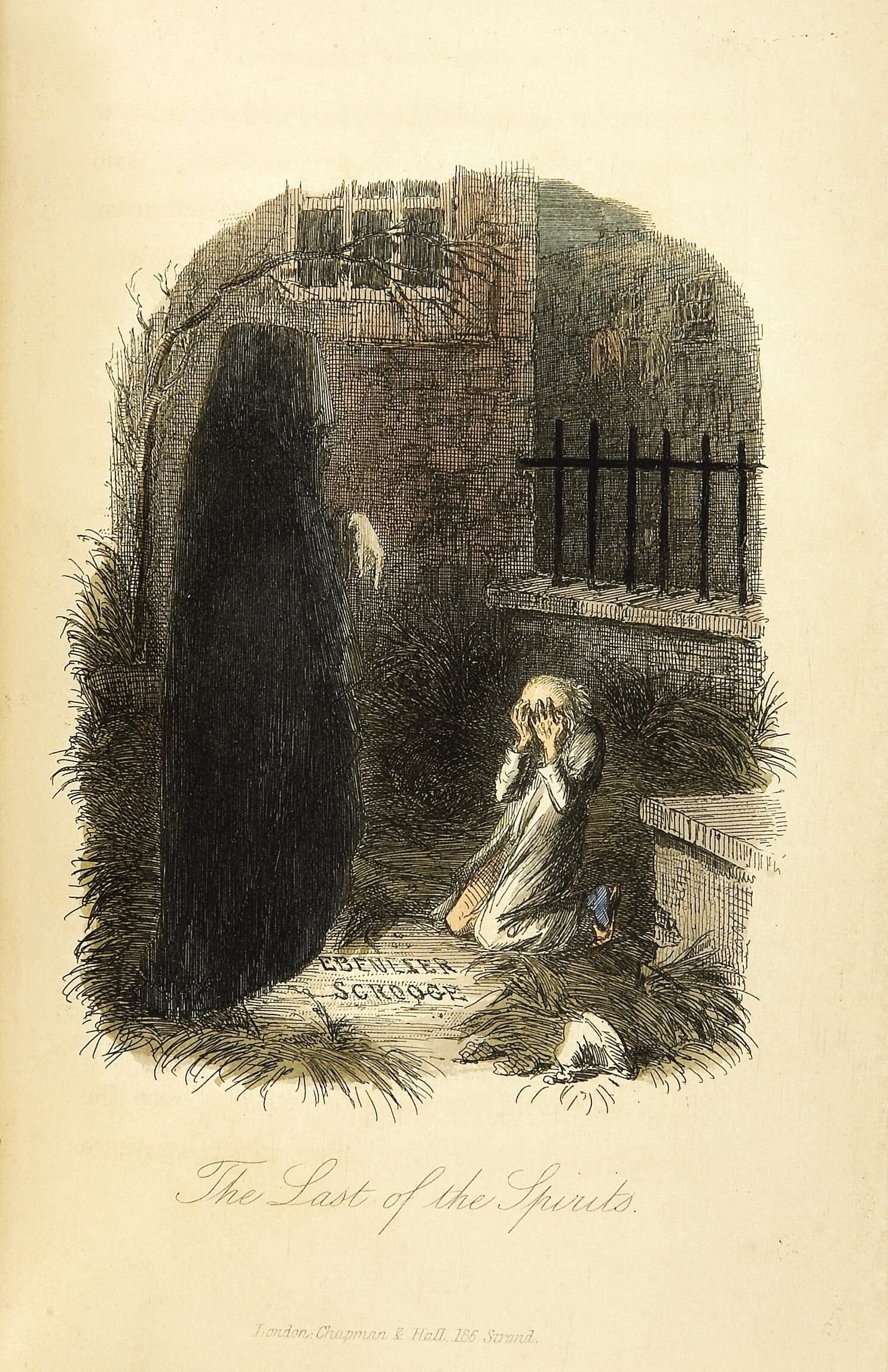

Illness in children is something that most people find particularly horrible, especially people who are parents themselves. When someone elderly becomes ill, it remains tragic, but it's easier for people to rationalize it, saying that it's that person's time. When someone one's own age becomes ill, which most of us will begin to experience anywhere between the ages of thirty and sixty, it can be a shocking reminder of one own's mortality, and it can be particularly horrific when families lose a caregiver or a provider. When a child becomes sick, however, there's the added aspect of that most terrible of all forces: unfairness. Small wonder, then, that literature is full of examples of illness and death in the young being used as a storytelling device, as it is in the case of Tiny Tim in Dickens' A Christmas Carol. In A Christmas Carol, the big turning point for Scrooge is when he sees that Tim is fated to die; by the time that the Ghost Of Christmas Yet To Come leads Scrooge to his own grave, Scrooge already claims to have had his change of heart. Seeing his own fate cements his conversion, but seeing a child's death was, to my reading, the most powerful trigger of it. As with any effective storytelling device, we can get a lot of use out of this tool in our own stories. I can't count the number of times that a storyteller has put a child, an innocent, or a character's loved ones into harm's way because it was the quickest and most efficient way of giving the players a sense of urgency and desperation. It's cliché and easy to overuse, but it works, so use it. For it to work, however, there needs to be one element that many storytellers fail to adequately explore: the player characters need to be able to do something about it. If they can't change an outcome, the incentive to act is much less.

As for why this is on my mind at the moment, today I found myself engaged in a half-hour long discussion about whether or not Ebenezer Scrooge's change of heart could actually have resulted in him saving Tiny Tim's life and averting the future foretold to him by the Ghost Of Christmas Yet To Come. I'm at a loss to say whether this is evidence that I lead an amazing life or a ridiculous one.

Before we can decide whether Scrooge could have saved Tim, we have to have an idea of what Tim's illness was. If you're at all familiar with the academic world, it likely comes as no surprise that a number of pediatricians over the years have tried to make the diagnosis. Similarly, you won't be surprised to learn that the diagnosis has been contentious. Dickens, for reasons that I can scarcely imagine, didn't choose to present Tim's symptoms and physical exam in a clear and medically precise format, opting instead to describe Tim's illness in a vague manner which could only be called "narrative" and which is therefore not fully helpful to us as modern clinicians. Donald Lewis in 1992 and Russell Chesney in 2012 wrote what I consider to be the seminal articles on the topic, although a number of others have contributed to the discussion. Most authors make similar observations: Tim had unusually short stature, a clear bodily asymmetry, and intermittent weakness and although we see him with a severe cough in the story, it's difficult to say whether this was part of, or in addition to, his primary diagnosis. Not all of these observations are based on Dickens' book, though; the famous image of Tim hobbling on a single crutch, which suggests a unilateral illness, comes from pictures drawn long after Dickens himself was dead. We have only one other piece of information to guide us: whatever illness Tim had would have been lethal within one year, but was treatable during that time, so it's much less likely that Tim suffered from, say, cystic fibrosis, or another wasting respiratory disease which would have had an even grimmer prognosis back then. The most popular diagnoses have been renal tubular acidosis, rickets or other forms of undernutrition, tuberculosis, polio, cerebral palsy, spinal cord disorders (inborn or traumatic). Chesney's paper makes an elegant argument that Tim suffered from both rickets and tuberculosis, based not only on an analysis of the London of that era, but also based on Dickens' own life experience. Obviously, we can never know the answer, but we have a respectable differential diagnosis to go on.

Scrooge could easily have been single-handedly responsible for saving Tim's life from any one of these illnesses or any combination thereof. He was in a position to provide the most important predictor of good health is that era: money. Renal tubular acidosis is a group of disorders that can cause bone growth problems, chronic illness, and an increased risk of respiratory failure; in that era, it was known to be treatable by supplementing the diet with various salts. Rickets would account for Tim's small size and bony deformity and would have also have predisposed him to recurrent lung infections and pneumonia if it impaired his ability to exercise and move about, and although it wouldn't be reversible, physicians of that era knew it would be treated with proper diet and cod liver oil. Tuberculosis could have been treated by helping to get Tim out of the slums of Camden Town, and Scrooge could no doubt afford to send Tim to a proper treatment facility. Similarly, London in the nineteenth century had numerous centres which were theoretically equipped to treat (or at least improve quality of life and length lifespan) victims of disorders like polio and CP, and these diseases as well would surely have improved along with Tim's better diet. With the power of money, Scrooge could have treated any disease that could have accounted for Tim's symptoms, at least for an extra year or so.

And thus, Dickens paints us a moving portrait of one man's redemption, brought on in large part because he didn't want to watch a sick boy die. It no doubt helped his redemption that he wanted to save his own life, too, but then, a good storyteller always gives a character multiple motivations to solve the same problem.

More than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on December 28, 2013. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.