In Search of Atlantis

There is, perhaps, no legend that has been as widespread, persistent, and well known throughout human history as that of the lost continent of Atlantis. This legend is exceptional in that it is not just about something old, it is a story that is itself very old, and one that is about something even older.

Introduction

There is, perhaps, no legend that has been as widespread, persistent, and well known throughout human history as that of the lost continent of Atlantis. This legend is exceptional in that it is not just

about

something old, it is a story that is itself very old, and one that is about something even older. It is thus not too surprising that the story of Atlantis has been examined and re-examined so many times and by so many people over the centuries since it was first told.

Roots of the Legend

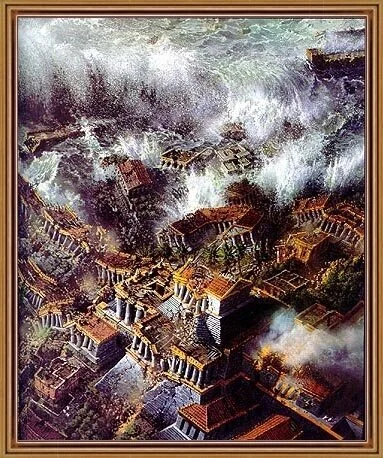

Our earliest known detailed account of Atlantis, the "island of Atlas," comes from the philosopher Plato, who wrote about it in two of his dialogs around 360 B.C., nearly 2,400 years ago. According to Plato, Atlantis was a naval power located on a great island beyond the Pillars of Hercules that conquered large parts of Western Europe and Africa many hundreds of years before his own time. After a failed attempt to invade Athens, a powerful Atlantis sank into the ocean "in a single day and night of misfortune" and, amongst other things, became an impassable shoal that made exploration of previously navigable ocean impossible. Plato himself, however, claimed that his version of the story originated with Egyptian priests who told it to a visitor from Athens some two centuries before.

Interestingly, while people in our own age often conceive of Atlantis as the archetype of an ideal society, Plato used it as an example of the opposite of a perfect culture and, among other things, described it as being a warlike and tyrannical state that enslaved those it conquered.

Today, some believe the Atlantis legend to have a basis in fact while others dismiss it as merely a fairy tale. This was, in fact, the case even from Plato's era onward, and scholars since then have been divided in their opinions on the matter.

American Additions

From the 16th century onward, following the discovery of the New World by European explorers, there was a renewed interest in the Atlantis legend, and attempts to correlate its details with the lands of the Caribbean, North America, and South America.

In the middle and late 19th century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars formally proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to the Mayan and Aztec cultures, a movement that became known as Mayanism. This led to a variety of narratives and publications, many of which attempted to rationalize the discoveries within the context of the Bible. Many also had somewhat bigoted undertones, in that they were based on the assumption that the indigenous people of the region were inferior and incapable of building the great cities of Central America and that they must instead have been the work of a now-vanished but superior race that originated in Atlantis. Some even claimed to have identified connections between the Mayan and Greek languages or between the cultures of Central America and Egypt.

The most influential voice to come out this movement was a retired Minnesota congressman and lieutenant governor named Ignatius Donnelly, who in 1882 published a weighty book titled Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. This popular book played a big role in stimulating interest in the subject and attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from Atlantis, which Donnelly saw as a technologically sophisticated, more advanced culture.

In his book, Donnelly drew parallels between creation stories in the Old and New Worlds, attributing the connections to Atlantis, which he believed to be the location of the Garden of Eden. And, as implied by the subtitle of his book, Donnelly also postulated that Atlantis was destroyed by the Great Flood of the Bible. He is, in any event, credited as the "father of 19th century Atlantis revival" and quite possibly the main reason that interest in the legend endures to this day.

Possible Locations

Over the millennia, many believers in the legend have attempted to pinpoint the location of Atlantis. Plato himself claimed that Atlantis was an island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and that a great unknown continent lay beyond it (shown here is a map by scholar Athanasius Kircher, who included it in his 1669 book Mundus Subterraneus; note that the map is oriented with south at the top).

Plato included quite a bit of physical description in his accounts of Atlantis that subsequent investigators have drawn upon for clues. He claimed, for example, that the island was about 345 miles long from north to south, and about 230 miles from east to west. He also described it as being predominantly mountainous in its northern half and as having a great plain in its southern portion.

Over the past century in particular there have been dozens of locations proposed for Atlantis, many of them not even within the Atlantic Ocean as Plato specified and as its name implies. Many of these locations are not actually based on scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, and some have even been identified through psychic or other paranormal means. And, while many of these proposed sites do indeed share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis legend, none has verifiably been demonstrated to be a true historical Atlantis.

Proposed locations for the lost continent have included Sardinia, Crete, Sicily, Cyprus, Malta, and various locations in Turkey and north Africa in the Mediterranean; just outside the Pillars of Hercules in southwestern Spain, in the vicinity of Cadiz; the Canary Islands; the Madeira Islands; the submerged island of Spartel near the Strait of Gibraltar; a sunken island in the North Sea or the waters of Sweden; in the Celtic Sea and with a possible connection to Ireland; an alleged sunken city off a peninsula in Cuba; the Bermuda Triangle; various areas in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, including Indonesia; the continent of South America; a legendary lost continent off the coast of India; and Antarctica.

We are going to look at three areas in particular that have seemed like especially compelling candidates for Atlantis.

The Bahamas

The Bahamas have, for a number of reasons and at various times, been suggested as a possible location for Atlantis — and, of course, a place of that name can be found there today, perhaps with some justification.

Many of you have undoubtedly heard of Edgar Cayce, an American psychic who would have visions while in a trancelike state and who was influential in the mid-20th century. He claimed that many of the people for whom he performed "life readings" were reincarnated from people who had lived on Atlantis, as a result of being able to tap into their collective consciousness, he was able to provide many detailed descriptions of the lost continent. He also asserted that there is a "Hall of Records" beneath the Egyptian Sphinx that holds the historical texts of Atlantis and that Atlantis would "rise" again in the 1960s.

Then, in 1968, his predictions seemed to be conformed when divers discovered an underwater structure that was dubbed the Bimini Road, a portion of which can be seen here. Two other similar structures have subsequently been discovered running parallel to this stretch of apparent pavement.

The Bimini Road itself is the largest of these three linear features is about a half mile long, with a pronounced hook at its southwest end. It consists of stone blocks measuring as much as 10 to 13 feet in width. This discovery, along with other physical characteristics and especially Edgar Cayce's predictions, convinced many that the Bahamas were indeed the lost continent of Atlantis. Be sure to come to my talk on pre-Columbian transatlantic traffic, however, to hear some alternate theories about the Bimini Road.

The Azores

Another proposed location for Atlantis are the Azores, which are especially promising for a number of reasons, a key one being that they are pretty much where Plato and his adherents described the lost continent as being.

Our Ignatius Donnelly was among those convinced that the Azores, consisting of nine islands in the Atlantic Ocean about 1,000 miles west of the Pillars of Hercules, were in fact the mountainous peaks of sunken Atlantis. Some of his evidence of this, for example, was that Plato described the cities of Atlantis as being built with white, red, and black stone, and that rock of these colors, including black lava rock, can be found on the islands. Plato also mentioned the presence of hot springs on Atlantis, another phenomena that can be found in the Azores. He also correlates Plato's descriptions of mountains and plains with their presence and locations on the Azores, ostensible similarities of climate, and a number of volcanic eruptions that affected the islands in historical times.

Santorini/Thera

One of the most compelling proposed locations for Atlantis is the island of Santorini, located in the Aegean Sea north of Crete. This island at the heart of the Minoan civilization was, in fact, violently destroyed by a volcanic eruption around 1600 B.C., and its obliteration led to the eventual demise of the culture it was part of. When the ruined city of Akrotiri was discovered on the island in 1964, along with evidence of a sophisticated prehistoric culture that included elegant frescoes, Santorini became for many a favored probable location for Atlantis.

The circular configuration of Santorini has caused some of what Plato wrote to resonate with those seeking the lost city. He says, for example, that at the center of the capital of Atlantis was a mountain carved into a palace and it was enclosed within three circular moats of increasing width and separated by rings of land and connected with bridges.

Popular Culture

The idea of Atlantis has been incorporated into innumerable books, films, and other works, all of which have helped to perpetuate the legend and continuously reinvent the legend. Some of you may recall that Atlantis appeared in a number of Jules Verne stories, for example, including 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island, and that there were glimpses of its remains in the films based on them.

Other Legends

There have, over the centuries, also been legends of other lost or mysterious continents, and it is not always clear whether they have their roots in the folklore of various peoples or are the creations of latter-day scholars and writers.

They include Mu, a lost continent in the Pacific Ocean; Lemuria, a sunken land in the Indian Ocean; Hyperborea, a land believed by the ancient Greeks to be located at the top of the world; Valusia, a prehistoric land that appeared in a number of stories by swords-and-sorcery author Robert E. Howard; and R'lyeh, a sunken continent in the Pacific inhabited by pre-human monsters that was at the heart of several stories by horror author H.P. Lovecraft; Meropis, a land a of giants located beyond the ocean that was described by the historian Theopompus of Chios just a few decades after Plato's writings on Atlantis; the New Atlantis of Renaissance writer Francis Bacon; and the Utopia of Sir Thomas More.