Quarry ('City Builder' Tradesman Place)

The Quarry is a rules-free description of a specific sort of Craftsman Place that might be found in many different sorts of communities and cultures. It is formatted like the more than 70 places found in the Skirmisher Publishing LLC universal sourcebook City Builder: A Guide to Designing Communities, and intended to stand by itself or serve as bonus content to that volume. Both this article and the City Builder project overall are designed to be compatible with the needs of almost any ancient, Dark Ages, Middle Ages, Renaissance, fantasy, or other role-playing milieu.

A quarry is a type of mine, generally open-pit but sometimes subterranean, from which stone or other sorts of minerals are extracted. A quarry is often cut into the side of a rocky hill, exposing a vertical face of newly-cut bedrock from a particular type of sculptural or building stone, gravel, pebbles, or sand can be removed.

Other sorts of quarry might take the form of a pit in the earth, where the workers have dug down to remove an overburden of dirt and poor-quality material from the desired formation of bedrock, or resemble a shallow and high-ceilinged sort of mine, in which the workings remain entirely underground. A clay pit, typically located in low-lying river deposits, function similarly to more traditional quarries.

Celebrated quarries include Mount Pentelikos, which supplied marble for the buildings of the Acropolis in Athens; Penrhyn Quarry, the largest slate quarry in Wales and a flashpoint of labor activism; the vast underground quarries beneath Paris; Rano Raraku on Easter Island; and Marble, Colorado.

Because its products must often be removed in large slabs — particularly when single pieces are desired for monumental sculpture, lintels, or foundation blocks — a quarry requires easy access right up to its work areas for heavy wagons of whatever other means of conveyance are being employed (e.g., log rollers). Thus, more than other sorts of extractive sites, a quarry is likely to include broad horizontal access tunnels called adits, cuttings, built-up roads, or horse-drawn tramways (which, historically, encouraged the earliest uses of railed vehicles in some nations).

Once exposed to air and removed from a rock vein, certain types of stone change their characteristics significantly, from an initially soft and easily-worked state to a much harder consistency. This encourages the stonemasons who wish to use these rocks to set up workshops within the quarry to finish most of their stone blocks on site.

Architects generally seek, if they can, to obtain building stone of suitable quality from nearby quarries — supplemented by any materials they can reuse from demolished or ruined structures already on their building sites — as the greatest part of the cost and labor of acquiring cut stone often consists in transporting the blocks overland to the building location. Some stone, however, is so unique in its beauty or symbolic significance to a particular project that it justifies transportation over many days journey, or even a river or sea passage that may require purpose-built ships or oversized barges. Occasionally, also, such projects employ powerful magic, such as the spells with which Merlin was said to have brought the components of Stonehenge from Ireland. Similar tales are told concerning Nan Madol in Ponape.

Types of stone most commonly quarried include granite, marble, and slate, which have hard-wearing surfaces, split cleanly into rectangular blocks, and show a pleasant grain and color that is sometimes enhanced by interesting veins and inclusions in the case of ornamental facing stones. Sandstone (such as brownstone), limestone (such as Jerusalem stone), and volcanic tuff are also used in many regional building traditions and, when quarried in great abundance, may give a distinctive character to the architecture of a city or a set of towns.

And some of the most favored types of stone can be exported to other nations, where, due to their cost, builders might only use them for corners, wall surfaces and veneer, and sculpture, making up the bulk of structures with locally-cut blocks, rubble, or brick.

Other stones, such as soapstone, flint, and chalk, provide everyday items and industrial materials rather than building components.

Within nations that commonly build or sculpt in stone, any substantial stone-built village or town needs at least one quarry within easy transport distance, and a large city or metropolis likely favors several bulk-stone quarries and at least one well-known source of particularly fine stone for its sculptures and significant buildings. In rural regions, intermittently-worked quarries may have supplied materials for several nearby large edifices of stone, such as temples and castles, or a large and well-known quarry may export its produce to form the foundational industry of a village or town.

As quarrying is hard, isolated, and often dangerous work, it is often relegated to convicts, prisoners of war, or slaves. It is also possible, however, that small groups of skilled workers might be able to exploit a limited resource that sells for a high price and thereby earn an independent living superior to what they might otherwise be able to achieve.

Dwarves show great ability as quarrymen, as they do with all stone-working trades, although in their own estimation this is only a second-rate profession compared to the glories of stonework carved in situ from the living bedrock. Other fantasy races with an affinity for stonework and mining might operate quarries in a given setting, most notably Gnomes, Kobolds, and some Giants.

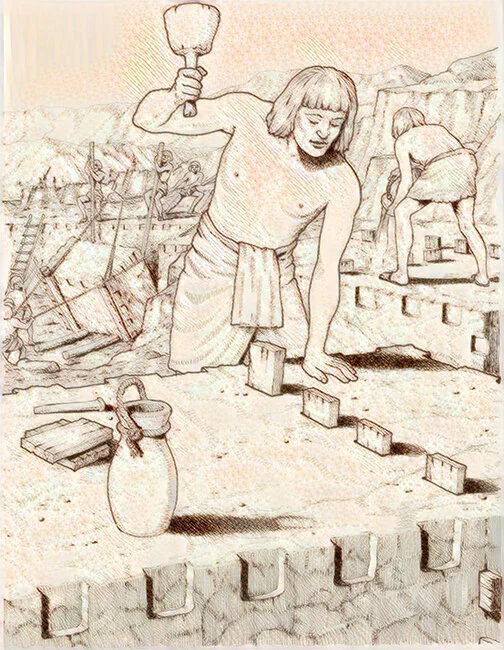

Quarrymen, working from scaffolds, split out large sections of rock, typically by cutting a series of slots to each side and below a chosen piece, drilling a row of holes along the desired break line, then splitting the rock between them using hammered wedges (as pictured here), water poured into the holes and allowed to freeze overnight, or alchemical compounds that corrode, crack, or blast apart the stone. The work crew may use ropes, pulleys, rollers, and ramps to lower each stone block safely to the floor of the quarry, particularly if working at a higher level where the rock would break apart if simply dropped.

Sheer cliffs with unstable edges, minor rockfalls, and large-scale collapses pose deadly risks to workers or to incautious visitors to a quarry. Inactive workings collect rainwater in deep, stunningly cold pools, where those who swim or fall in unprepared can easily drown. And years of exposure to the dust and chips from broken rock abrade the skin and lungs of lifelong workers.

Because stoneworking tools make quite effective weapons, a quarry worked by slaves or prisoners needs a substantial and attentive guard force. If a quarry uses alchemical substances to break rock, criminals or plotters can use the same methods to get into secure vaults, collapse buildings, or otherwise cause mass destruction, so the owners typically keep these compounds in securely-locked cases and impose stringent accounting procedures to ensure no amounts go missing. Beyond these special circumstances, a quarry’s product is only valuable in large quantities that are impractical to carry away and its tools are not especially valuable, so its security arrangements might end with a fence and warning signs to deter outsiders who might be seriously injured or killed. Because nobody other than quarry workers ought to be anywhere on the site, trespassers might fall victim to operations such as rock-blasting that take no account of their presence.

Adventure Hooks

* Quarry workers might unearth the remarkable and valuable skeleton of a giant or primordial beast, or even the still-living body of an immortal creature that has survived uncountable ages trapped in the stone. Scholars or cultists interested in the find may intrigue against each other to take possession of it, even resorting to fraud or violence. And, a creature not so inert as it initially appears, may become animate at night to slay and feed among the local inhabitants.

* Villagers ask the party to find a peasant lad who disappeared some time ago. Unfortunately, the young man was chased (e.g., by bandits or some frightful creature) over the edge of a disused quarry, where he drowned. His body may never be found and the full circumstances of his death ascertained unless the players can assemble obscure clues to find the location where he died.