Investigating the Mystery of Banded Mail

As someone who has long studied medieval drawings, sculptures, and other artworks, several years ago I became aware of a historical mystery that I have since contemplated and attempted to solve to my own satisfaction.

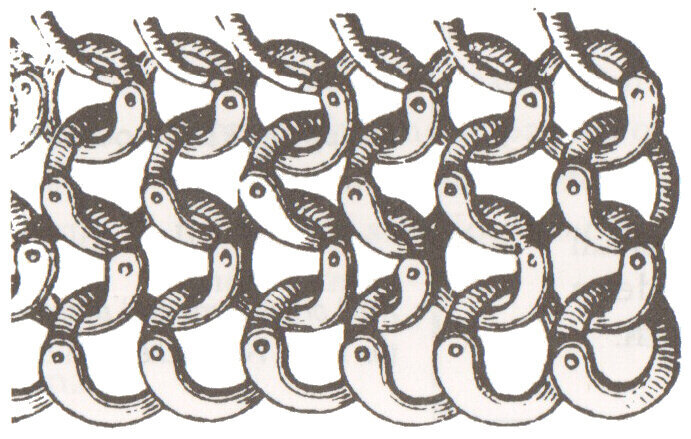

Anyone who examines such items with an eye toward deriving information from them will undoubtedly notice that many figures are, not surprisingly, shown wearing chainmail fashioned in a familiar and classic four-in-one pattern. Some European illustrations and sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, however, clearly depict people wearing a distinctly different chainmail pattern, with alternating rows of links separated by horizontal bands or alternating rows of solid disks. Armor depicted in this way has commonly been referred to as "banded mail" (and old-school gamers may recall that an armor of this type appeared in the 1st and 2nd editions of the Dungeons & Dragons RPG).

Some historians believe that banded mail is chainmail reinforced with small plates of metal, a technique prevalent in Eastern European armor. Russian bachteretz armor, for example, is made up of a dozen or more such rows across the torso and abdomen and resembles suits of Indian reinforced chainmail, which include even more such plates. Not only was such armor rare in Western Europe, however, but the banded mail described here is shown mostly on limbs and joints, not on the torso as was common in India and Russia.

"Double mail" is another possible explanation for banded mail. Regular chainmail is made up of interlocking metal rings with each ring connected to four others (i.e., a four-in-one pattern of five rings). In this configuration, the interior area of a ring is about twice the size of the area taken up by the links of the four interlocking rings. But double mail links are thick and are more than half as wide as the interior diameter of the link and, when interlinked, there is no space between the individual links. (Double mail is sometimes incorrectly assumed to be based on an ensemble of more than five rings, such as an assemblage of seven rings [i.e., a six-in-one pattern], but such an arrangement of chain links is effectively useless for armor because it will not lay flat, a necessity for chainmail.) Banded mail may thus have been regular chainmail reinforced with sections of double mail.

Persian and Indian chainmail is often made up of an assemblage of brass, copper, and steel links arranged in decorative patterns, which may be another explanation for banded mail. Usually, such decoration is confined to secondary pieces of armor, such as the aventail, a short chainmail cape that hangs from the back of a helmet to protect the neck, but decorated links can appear at any place on a suit of mail, including the leggings and the torso. Such embellishments are often in the form of abstract designs but they can also be simple pictures, and some of the most dramatic embellishments are on Muslim armor and spell out words in Arabic.

Beyond these sorts of embellishments, however, there is little physical evidence for a discreet species of banded mail, as is depicted in two centuries of European art. Furthermore, in A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor, author George Cameron Stone insists that banded mail is of "a construction that is manifestly impossible," presumably because the reinforcements shown in depictions of banded mail would have impeded a warrior's flexibility. So if such armor is of an impossible or improbable construction and if there are no actual examples of it in existence, why does it appear in works of art?

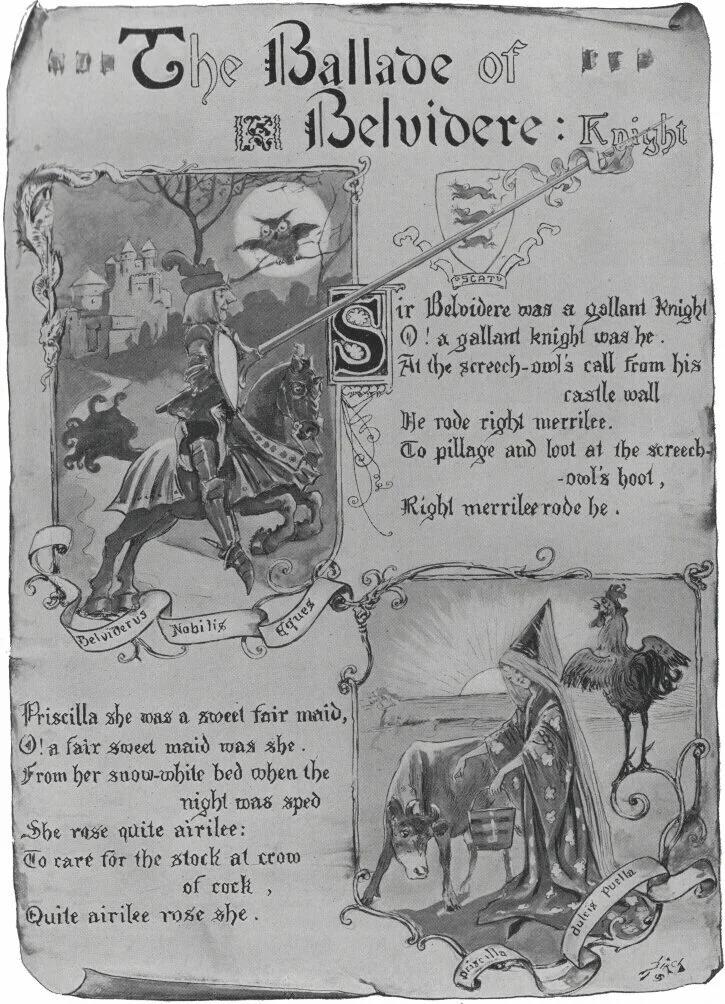

Most likely, banded mail is nothing more than an artistic convention associated with the age. Today, painting, sculpture, illustrations, cinema, and the stage consistently depict aspects of life inaccurately and many such inaccuracies are so widespread today that they do, in fact, qualify as artistic conventions. There is no reason to think artists of the past were any more conscientious. Were all women exceptionally full-figured during the time of Rubens? Certainly not. Are most of the women in our society painfully underweight, as they are often depicted in modern media? Of course not. If plentiful subjects like women are so regularly misdepicted, how much more likely it is that weaponry, something that most artists have no direct experience with, will be inaccurately represented. Banded mail shown in the art of the 1100s and 1200s perhaps looks the way it does because artists of the age decided it looked "cool," not because armories really made such armor or because soldiers really wore it.

Obviously, there is no better way to learn about the construction of various arms and armor than to examine samples of such items directly. Short of direct examination, illustrations often provide an informative record of the armaments of the past, and in many cases tell us almost everything we know about the weapons of a particular age or people. Nonetheless, depictions like those of banded mail need to be examined critically, and the information we glean from them tempered with direct evidence and simple logic.