Ancient Extreme Sports

“Extreme” is a word that people use today more than they used to with regard to athletic activities, and the passions excited by them in participants and fans alike can, in fact, be excessive, as unrest in the wake of losses — or even victories — periodically demonstrates. Since the dawn of civilization, however, athletes have played sports of various sorts, crowds of people have watched and cheered for them, and devotion to one team over another can lead to all sorts of bad behavior.

Sports themselves have their origins largely in military training, and were used both to assess the capabilities of individuals and serve as a mechanism for physical fitness, building teamwork, and encouraging leadership. To the extent that people today might like to think of various sports as being “extreme,” who wins or loses actually tends to matter very little, whereas in the past such activities were often preparation for and an adjunct to actual combat. And, in some of the most dramatic examples from antiquity, serious injury and even death were a regular occurrence.

We are going to look at the athletic traditions of a number of different ancient peoples today, starting briefly with the Sumerians and Egyptians before moving on in more detail to the Greeks, the Romans, and then, finally, the Byzantines. While you will certainly be familiar with some of the sports we discuss today, I have endeavored both to include information about them that you probably do not know, and to cover a couple of sports that are probably completely new to you.

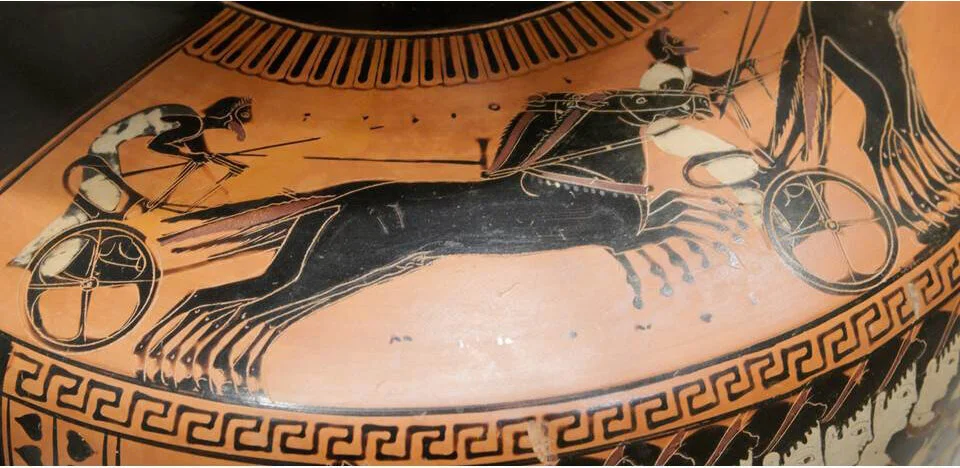

The black-figure Greek image of chariot racing that we can see above is a detail from late 6th century B.C. water jug from Athens.

ANCIENT SUMER

Boxing and wrestling are among the martial athletic activities depicted in artworks from the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia, in what is today Iraq, probably going back at least 5,000 years, and may indicate that these pursuits originated in this region.

We can see one of these below, a bas relief showing three pairs of wrestlers, that dates to around 3000 B.C.

Another Sumerian piece, a cast bronze statuette dating to around 2600 B.C. that might have served as the base of a vase and which is housed in the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, shows two figures in a wrestling hold. This and the piece shown here are, in fact, some of the earliest-known depictions of athletic activities anywhere.

Such references appear in Sumerian literature as well. Cuneiform tablets dating to around 2000 B.C. that bear the Epic of Gilgamesh, for example, provide one of the first written references to sporting activities, and describe Gilgamesh engaging in a form of belt wrestling with the beast-man Enkidu.

Cuneiform tablets have also been discovered in which the Sumerian king Shulgi, who ruled from the city of Ur from about 2029 B.C. – 1982 B.C., boasts of his prowess at athletics.

ANCIENT EGYPT

As a result of tomb paintings, carvings, and other durable forms of historical record, we know that ancient Egyptians practiced numerous well-developed sports.

Monuments dedicated to the pharaohs dating to around 2000 B.C. at the Beni Hasan historical site in central Egypt, for example, depict a number of athletic activities, including wrestling, weightlifting, long jumping, swimming, rowing, archery, fishing, and various kinds of ball games. Other sports we have existing depictions of from Egypt include javelin throwing, high jumping, and what appears to be a form of snooker or pool.

What we are looking at here is a depiction from about 2400 B.C. of two wrestlers that appears on the wall of a tomb for two royal servants, Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, at the Saqqara burial complex near Cairo. For clarity, the figures have been rendered in black and white here, but in the original they are both presented in shades of red, the traditional color used for depictions of men in ancient Egyptian art.

ANCIENT GREECE

Numerous depictions of ritual sporting events have been found in the artworks of the Bronze Age Minoan culture, particularly on the Aegean islands of Crete and Santorini,

and we can see two of my personal favorites here.

On the left is a fresco from the village of Akrotiri on Santorini from about 1650 B.C., which shows two youths boxing.

On the right, from about 1500 B.C. and the palace of Knossos on Crete, we can see a fresco that depicts gymnastic bull leapers. We actually had a copy of this larger image hanging on our wall the whole time I was growing up, so it is, in fact, among my earliest memories.

ATHLETIC FESTIVALS (ANCIENT GREECE)

Ancient Greece, however, is probably much better known for its great athletic festivals, which may have their origins in funeral games of the Mycenean period, between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. We have actual literary support for our insights into the basis for such festivals, beginning with the Iliad — Homer’s account of the Trojan War — which contains extensive descriptions of the funeral games held in honor of slain heroes, such as those staged for Patroclus by Achilles.

During this period, sports are described as an occupation of aristocrats, who have no need to engage in manual labor. In the Odyssey of Homer, for example, king Odysseus of Ithaca proves his royal status to king Alkinous of the Phaeacians by demonstrating his skill at throwing the javelin.

Recurring sporting events appear to have first been formally instituted in Greece in 776 B.C. with the Olympic Games, which were celebrated continuously in Olympia for nearly 1,200 years, until A.D. 393, and for which victors received laurel leaves as prizes. These games were held every four years, a period of time that came to be known as an Olympiad and used as a unit of time in historical chronologies. While it began as a single sprinting event, the Olympics gradually expanded to include several sorts of races — to include running in the nude and in armor — boxing, wrestling, pankration, chariot racing, long jumping, javelin throwing, and discus hurling.

Other important athletic events in ancient Greece were the Isthmian Games, the Nemean Games, and the Pythian Games which, along with the Olympics, were the most prestigious festivals of this sort and collectively known as the Panhellenic Games.

Some games, such as the Panathenaia of Athens — a scene from which we can see depicted here — included musical, literary, and other non-athletic contests in addition to the regular sporting events. Another significant event was the Heraean Games, the first known sporting competition exclusively for women, which were held at Olympia as early as the 6th century B.C.

EPISKYROS (ANCIENT GREECE)

While sporting festivals might be held every one, two, or four years, ancient Greeks also engaged in a wide variety of athletic activities on a more regular basis, including a number of ball games, one of which was known as

Episkyros

.

This game was played between teams of 12 and 14 players each using a single ball, emphasized the importance of teamwork, was known for being fairly violent — especially in militarized Sparta — and was probably similar in many ways to rugby.

One account of the game, in fact, describes how a spectator who somehow ended up in the middle of a match had his leg broken.

Episkyros involved one team trying to throw the ball over the heads of the other. A white line called a skuros was between the teams and another white line was behind each team, and one of the goals of the game was to force members of the opposing team over the line behind them. A special version of episkyros was played in Sparta during an annual city festival that involved five teams of 14 players, primarily by men but also by some women.

Other ball games played in ancient Greece include Aporrhaxis, a game that used a bouncing ball; Ourania, a game that involved throwing a ball high in air; Mache, meaning “battle,” which might consequently have involved more physical contact than most other games; and Phaininda, which probably involved some element of subterfuge, as the etymology of its name appears to be related to the word for “deceit.”

Either Episkyros, Phaininda, or both later served as the inspiration for a Roman ball game called Harpastum, which we will look at presently.

What we are looking at on the left is an image of an ancient Greek youth practicing with a ball carved in low relief on the remains of a marble grave marker from about 400 B.C. that is now displayed at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which some of you may have seen while we were there.

At right was can see a bottle from about the same period bearing a depiction of the god Eros playing with a ball.

ANCIENT ROME

Of all the many sporting activities associated with ancient Rome, probably the one that comes to mind immediately for most modern people is gladiator spectacles, which at their extreme were a

bona fide

death sport. We will look at a couple of others presently, namely the afore-mentioned ball game

Harpastum

and chariot racing, but gladiator games would be conspicuous by their absence, so we are going to touch on them at least briefly.

A gladiator — literally a "swordsman," as this term is derived from “gladius,” the word for “sword" — was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the eras of Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals.

Most gladiators were slaves or prisoners of war who lived and practiced under grueling conditions at training facilities, while some smaller number were volunteers who risked not just their lives but also their legal and social standings by appearing in the arena.

Regardless of their origins, gladiators offered spectators an example of Rome's martial ethics and, by fighting or dying well, could inspire admiration and popular acclaim. They were celebrated in artworks and their value as professional entertainers was commemorated throughout the Roman world.

How gladiatorial combat originated is somewhat uncertain, but there is evidence that they might have begun with staged combats held in conjunction with funeral rites during the era of the Punic Wars in the 3rd century B.C. In the years following this, in any event, such spectacles quickly became a critical element in politics and social life throughout the Roman world, and their popularity led to increasingly more elaborate and expensive events.

Gladiator games remained a part of Roman life for almost a thousand years, reaching their peak between the 1st century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D. They finally declined during the early 5th century, after the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in A.D. 380.

So much is known about gladiator games that we will not spend any more time on them here, but I would be glad to take any questions about them you might have at the end of the presentation.

This dramatic image of a Roman gladiatorial spectacle is an 1872 painting by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, who specialized in themes like this.

HARPASTUM (ANCIENT ROME)

As noted previously,

Harpastum

was a ball game played in the Roman Empire that was inspired by earlier Greek games and which reportedly required considerable speed, agility, and physical exertion. Romans referred to it as “the small ball game” and used in it a compact, hard ball that was probably about the size and weight of a pomegranate.

Little is known today about the exact rules of Harpastum, but sources indicate that it was a violent game that often led to its players ending up on the ground, and the root word of its name means "carried away" or "seized," which certainly suggests at least in part how it was played.

A number of ancient writers refer to Harpastum in their works, and the general impression we can derive from their descriptions is of a game similar in many ways to rugby, as with its Greek predecessors. Additional descriptions suggest a line was drawn in the dirt, and that the teams would attempt to keep the ball behind their side of the line and prevent their opponents from reaching it. Ancient accounts of the game, however, are not precise enough to allow reconstruction of the actual rules in any detail.

One fan of Harpastum was the physician Galen, who said it was "better than wrestling or running because it exercises every part of the body, takes up little time, and costs nothing"; that it was "profitable training in strategy" and could be "played with varying degrees of strenuousness." Galen went on to say that when players faced each other in the game, “vigorously attempting to prevent each other from taking the space between, this exercise is a very heavy, vigorous one, involving much use of the hold by the neck, and many wrestling holds."

What we are looking at on the left is an ancient Roman fresco depicting a game of Harpastum. At right we can see a tombstone found in the ruins of a Roman military camp in what is now Croatia that shows a boy holding a Harpastum ball.

BYZANTIUM

Chariot racing was one of the most popular spectator sports among ancient Greeks, Romans, and Byzantines, but its extreme characteristics reached their peak in this latter society and so we have left our discussion of it until now.

Chariot racing was, suffice it to say, dangerous to drivers and horses alike and frequently caused serious injury and even death to both, incidents that added to the excitement of spectators.

In ancient Greece, women, who were banned from watching many other sporting events, were allowed to attend chariot races, which contributed to their broad appeal.

In ancient Rome, chariot racing was based on teams that represented different groups of financial backers and which sometimes competed for the services of particularly skilled drivers. Spectators generally chose to support a single team, identifying themselves strongly with its successes and failures.

There were initially four major factional teams of chariot racing, the Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites, differentiated by the colors of the uniforms in which they competed, which were also worn by their supporters. These teams and their affiliated fan clubs often became affiliated with various social, political, and religious ideas, and violence increasingly broke out between them. Roman and eventually Byzantine emperors appointed numerous officials to oversee these associations and tried use them to their own ends — sometimes, as we shall see, with lethal results.

After the fall of Rome in the late 5th century A.D., chariot racing faded in importance in the West. It continued to thrive for a time in the Byzantine Empire, however, where the traditional Roman racing associations maintained prominence and political influence for several centuries.

These associations became a focus for various social and legal issues for which the general Byzantine population had no other outlets, and combined aspects of both political parties and street gangs. They took positions on current affairs, such as religious issues or succession to the throne, and frequently tried to affect the policies of emperors by shouting political demands in between races. These groups became so powerful, in fact, that the military could not keep order without the cooperation of the hippodrome factions.

By the time the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great took power in A.D. 527, the only team associations with any influence were the Blues and the Greens. Justinian himself was, in fact, supported the Blues, and a number of aristocratic families who believed they had a more legitimate claim to the throne than he did were affiliated with the Greens.

NIKA RIOTS (BYZANTIUM)

In A.D. 531, some members of the Blues and Greens had been charged with murder in connection with deaths that occurred during the riots following a recent chariot race. Most of them were hanged but, on January 10, 532, two of them, a Blue and a Green, escaped and took refuge in a church, drawing an angry mob of supporters. In an attempt to calm the situation, Emperor Justinian commuted the sentences of the killers to imprisonment and declared a chariot race would be held on January 13. The Blues and Greens, however, responded by demanding that he pardon the two men entirely.

An angry crowd of fans arrived for the races at the Hippodrome, which was located next to the palace complex, allowing the emperor to preside over the event from the safety of his box there. Almost immediately, the crowd began hurling insults at Justinian and, by the end of the day, their separate cries of "Blue" and "Green" had become a unified chant of "Nika" or "Victory," and they began to attack the palace. For five days, they besieged it and set fires throughout Constantinople, destroying much of the city, to include its foremost church, the Hagia Sophia.

Some of Justinian’s opponents, who opposed his new taxes and lack of support for the aristocracy, saw the civil unrest as an opportunity to overthrow him. Controlled by the disaffected nobles, the rioters, who were now armed, also demanded that Justinian dismiss the officials he had charged with collecting taxes and rewriting the legal code and then declared that a nobleman named Hypatius would replace Justinian. In despair, Justinian considered fleeing but, possibly encouraged by his wife Theodora, he eventually rallied himself and formulated a plan involving three of his generals, Narses, Belisarius, and Mundus.

Carrying a bag of gold, Narses entered the Hippodrome alone and unarmed and, in the face of the murderous mob, approached the leaders of the Blues. He proceeded to remind them that Justinian favored them over the Greens and that Hypatius was a Green, and then gave them the gold, which prompted the Blue leaders to speak first quietly among themselves and then with their followers. Then, in the middle of Hypatius's coronation, they abruptly left the Hippodrome, leaving the Greens confused until imperial troops led by Belisarius and Mundus stormed into it and slaughtered everyone who remained there.

The Nika Riots were the most violent uprising in the history of Constantinople and, by the time they ended, they resulted in nearly half the city being destroyed and some thirty thousand race fans being killed. And, in the 1,500 years since, there have not been events more deadly or terrible prompted by or associated with a sporting event, extreme or otherwise.