Women's Work

When researching the history of medicine, it's easy to lose sight of the role of women, in part because female scientists have tended to be ignored and forgotten by historians. As a small step to changing that, here's some information on one of the most fascinating female healers of the medieval era, Trota of Salerno.

Dr. Eric Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC sourcebook, Insults & Injuries.

When researching the history of medicine, it's easy to lose sight of the tradition of the wise woman, or, for that matter, the role of women in general. The history of medicine has been male-dominated since the dawn of recorded history, which probably reflects three factors: that it has been harder for women to get formal education in most of the world; that female scientists have tended to be ignored and forgotten by academic historians; and that we know that a lot of the traditions we associate with "wise women," such as the old Celtic traditions, were deliberately erased by Christian civilizations. This is a somewhat interesting phenomenon, in that it parallels the well-known gender biases that pervade the role-playing game, video game, and comic book industries, as well as most of the rest of geekdom. When you go digging for it, though, you can find ample evidence of women who played vitally important roles in the development of medicine, sometimes as part of the wise woman tradition, sometimes in more academic and Westernized settings. It would be unfortunate if our games failed to reflect the simple truth that historically, female healers have been vital parts of society, and this should be doubly true in a campaign setting where women can become clerics and paladins as easily as men. Towards this, I've dug up some information on someone who I consider to be one of the most fascinating female healers of the medieval era, who I think can very much broaden the way healing is used in our games in a number of ways. That woman is Trota of Salerno, also known as Trotula de Ruggiero, and you can read quite a lot about her both at Wikipedia and in this article from the Journal of Medical Biography.

Trota is thought to have lived in what is now Italy, somewhere between the 11th and 12th centuries. She was trained as a Magistra Mulier Sapiens, literally a "teacher of female wisdom," about which we today have incomplete information but which is thought to have been a sort of general practitioner and surgeon with a particular expertise in women's health. In addition to being a masterful surgeon, she was said to be knowledgeable in gynecology and infertility, fields which were not terribly well understood in most other healing traditions of the time (and for that matter, aren't as well understood by most male physicians today as one might hope). She was noted to have a particular expertise in herbal medicines, and is known to have worked closely with specialized chemists and gardeners, who grew rare plants from which he derived a number of extracts. Her pharmacopeia contains a mix of classically European and Arabic remedies, since in the South of Italy she had access to that flourishing culture.

Like many of history's prominent healers, there's a good deal of uncertainty about who Trota was and what records she left because her books appear to have been expanded by later writers. Our records of Trota largely come from a collection of books together known as the Trotula, and we don't know how much of the Trotula was written by Trota herself. In fact, it was unclear if Trota was actually a real person for centuries, until data supporting her being an individual physician was uncovered just a few decades ago. A series of books are included in the Trotula, covering a range of topics. The writings discuss varied treatments which seem somewhat questionable to such today, such as dubious herbal remedies, blood letting, and purges, but her texts also reflect an understanding of observation and physical examination which are largely lost to modern physicians, who are relatively reliant on diagnostic tests and medical imaging. Her texts also have extensive discussions of the maintenance of beauty, which was felt to be of tantamount importance; this arguably unfeminist viewpoint makes more sense given that physical beauty was (and of course, often still is) presumed to reflect inner health and "harmony."

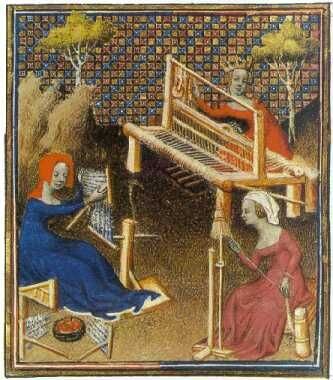

We can learn a number of important things from reading about Trota that might inform how we portray healing in medieval fantasy. First, from references to her fame in the Trotula, we know that she was treated with much the same respect as her male colleagues, which is quite surprising given the way that women had to fight to get that respect in the misogynistic eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. Second, we know that she was involved in writing (or at least quoted in) texts specifically on women's health, showing that people of the time certainly understood that men and women were different in some important respects. Third, we can see that the healers of the time saw a very strong link between beauty and health, especially for women. Lastly, the works tell us a bit about the organization of infirmaries and pharmacies of the era, including the existence (and profitability) of specially trained scholars whose sole role was to cultivate and provide rare plants for use as medicine.