Those Who Can't Do

The other day, I got into a surprisingly lengthy conversation with a colleague of mine as to how physicians got trained in the days before the sum of human knowledge was a few keystrokes away.

The other day, I got into a surprisingly lengthy conversation with a colleague of mine as to how physicians got trained in the days before the sum of human knowledge was a few keystrokes away. I suppose it says something that we both had so much difficulty imagining it.

My medical training predates the widespread use of smartphones, so I do remember what it was like to practice without having Wikipedia available every second of the working day, but I've never worked in a world where I actually had to go to the library if I wanted to look up the latest article in a scientific journal. There's actually a wealth of information available regarding how healers were selected and trained before me -- records that stretch back to well before the medieval period, to at least as far as ancient Greece and Egypt -- and reading some of those historical records can be really helpful for a storyteller who's building a world where people practice any sort of profession in an organized fashion. Of course, most of this information, I've never read, but it is both available and useful, if one has that sort of free time.

Broadly speaking, throughout history, there have been three different models by which healers pick up their art: self-discovery, apprenticeship, and organized education. Self-discovery was, obviously, the earliest form of teaching, and can therefore be arguably credited with being the foundation for everything that came after. Self-discovery is also the most limited form of teaching, both because it takes a long time, and because a lot of the things a person learns through trial-and-error are likely to be wrong. For example, suppose a would-be healer in ancient times sees two patients with the flu. To cure one of them, the healer offers up a prayer to Plaugg, the Gardnerian god of mediocrity, and to cure the other, he breaks their fingers with a hammer. One of them gets better, and one of them develops pneumonia and dies... it doesn't really matter which does which. There's every chance that the healer will "learn" that one treatment cures the flu and the other worsens it, and this sort of thing is why for centuries, the peak of human medicine was blood-letting and trepanation. When you're self-taught, you have the potential to make unimaginably huge strides, and you have the potential to make them in the wrong directions.

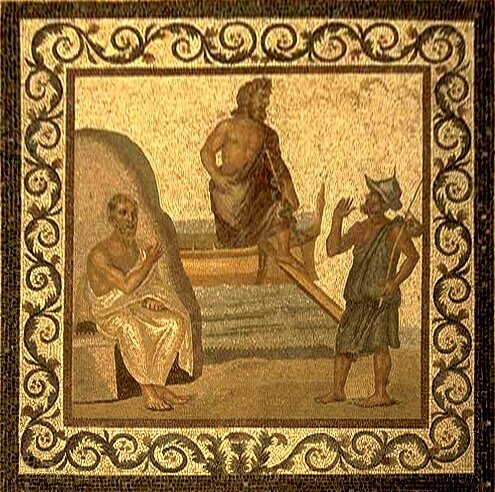

The next most advanced form of teaching professional skills is the apprenticeship. This term can be used to include all sorts of teacher-student relationships, be it the wise-woman who passes on her knowledge of herbalism or the 21st century oncologist who supervises a resident in the clinic. Assuming you have a reliable teacher, apprenticeship is an excellent way to learn, and most of my medical training, at least the important bits, have been in the form of one-on-one apprenticeship. In a medieval setting, particularly in a feudal civilization dominated by guilds, this is almost certainly the most common form of training of professionals, be they physicians, alchemists, blacksmiths, or thieves and assassins. The weakness of this system is that it's hard to produce large numbers of skilled people... and the people in charge of teaching may prefer having fewer students around so that they can hang on to their power. Apprenticeship has a big advantage over self-teaching in that there's someone around the "grade" the student, and there may even be some sort of formal certification process in more advanced societies.

Thirdly, you have formal education. Despite the fact that the university system didn't really catch on until nearish to the modern era, we know that organized medical schools go back at least a thousand years. The classroom setting lets you train the largest possible number of people at once, or at least, lets you pass on knowledge, which isn't precisely the same thing as passing on skills or competence. When the system works, it creates a large pool of individuals who are then ideally suited for an apprenticeship. When the system doesn't work, it creates a large pool of individuals whose heads have been filled with false beliefs and the absolute certainty that you only get from being told that "this is how everybody does it." This sort of organized teaching is probably fairly rare in a medieval game world, but a character with a university in their backstory always has a powerful resource to draw upon.

In my games, I see the training of healing to be some combination of the three. In medieval fantasy, organized teaching of healing is probably done mostly by good-aligned churches; this education may or may not come intermixed with a great deal of religious dogma which could help or hinder a healer's actual skill. Young clerics likely get some rudimentary teaching of the healing arts, and then those who wish to advance beyond casting Cure Moderate Wounds likely seek out advanced training which includes non-magical skills. A medieval-era society almost certainly already has some famous textbooks available, which set the standard of "proper" medicine. A world may or may not have formal medical journals; in history, organized dissemination of new research in journal form dates back to only the very late 1700's or so, but magical tools allowing rapid copying and circulation of publications might mean that such things catch on faster in a fantasy world. In a fantasy setting, the biggest obstacle to proper medical teaching is probably the abundance of healing magic, which probably makes most people feel that studying actual medicine is redundant at best and counter-productive at worst. Ultimately, the way in which a nation educates its healers -- or doesn't -- can add a bit of depth to a campaign and helps set a model for which all other professions are (or aren't) taught.

A little more than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on March 23, 2013. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.