There Wolf

Werewolves remain a serious problem in modern medicine.

Werewolves remain a serious problem in modern medicine.

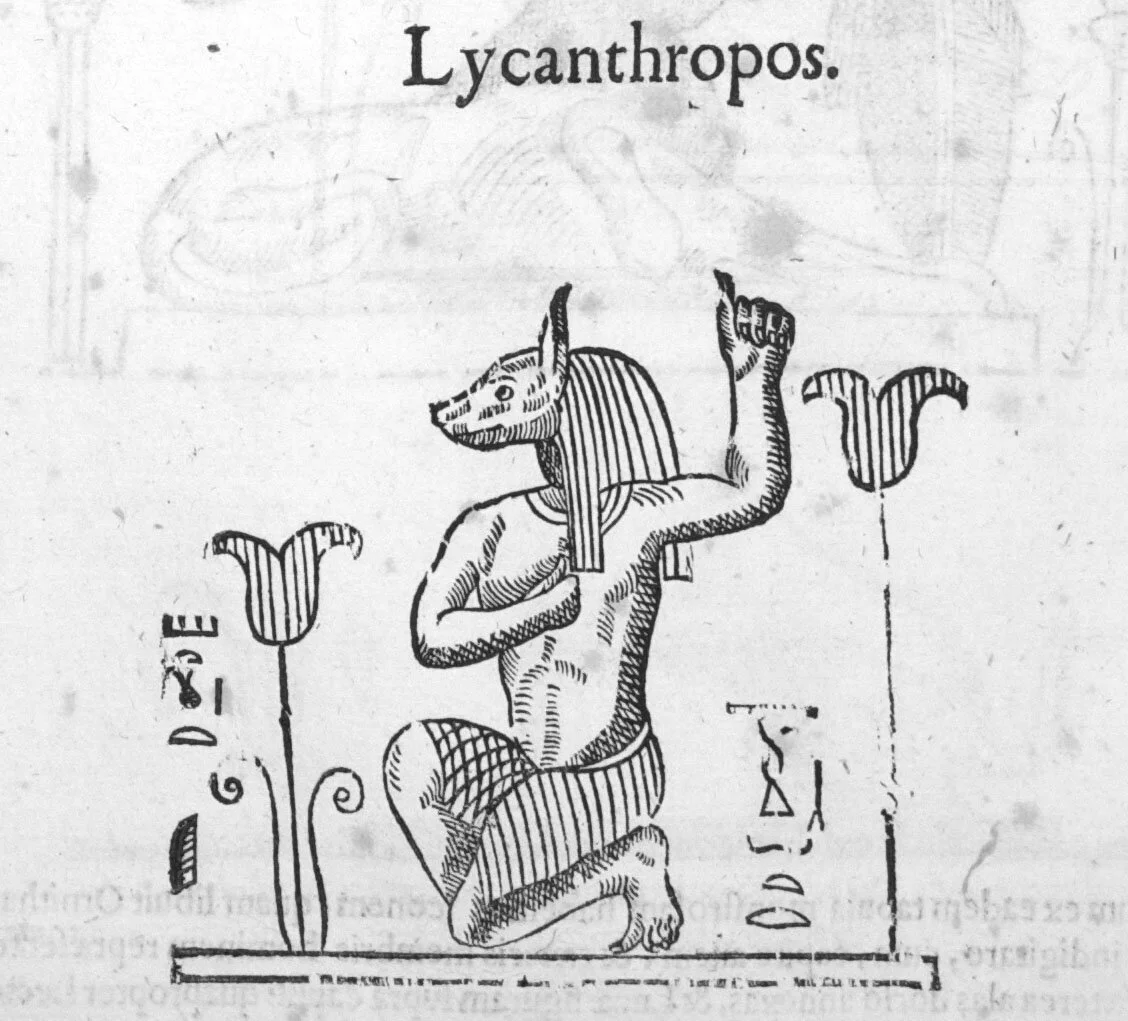

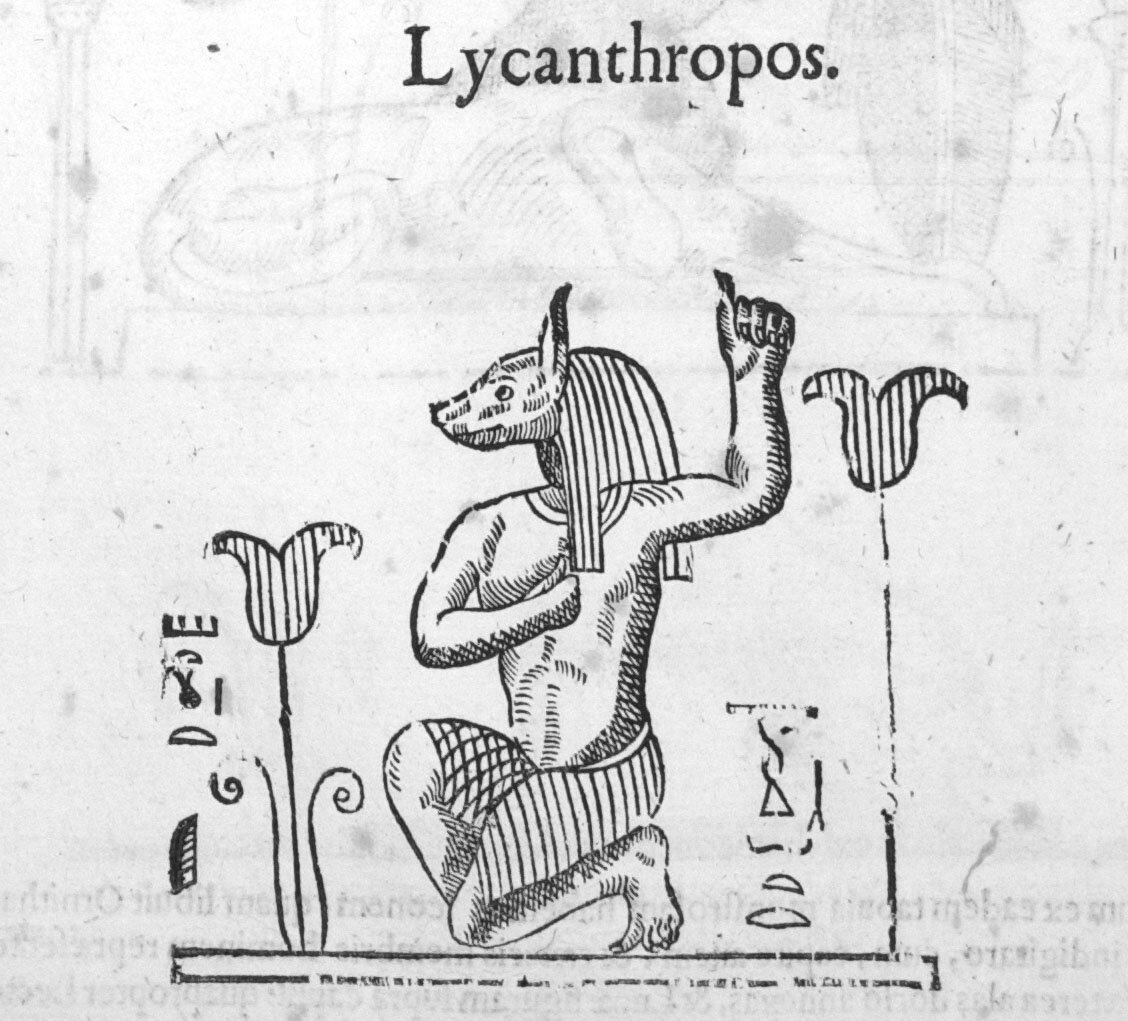

Ancient physicians were very familiar with lycanthropy, or as it was also known at various points in history, "cucubuth" and "lupinam insaniam." Modern medicine has a concept of "clinical lycanthropy." We call it "clinical" lycanthropy to distinguish it from actual real lycanthropy, which is fortunately very rarely diagnosed in most hospitals. Clinical lycanthropy refers to the delusional that one has turned, is turning, or can turn into an animal, and although it's fairly rare as a pure delusion, unlike the delusion of being the president or the messiah, it's one of those curious delusions that seems to occur in many, perhaps even all, cultures. Of course, "lycanthropy" isn't really an accurate term, for two reasons. First, in medical terms, a person who believes they turn into a wolf would more properly be said to suffer from "lycomania," mania being the Greek word for "crazy." Second, as everybody who's played White Wolf's World of Darkness knows, not every shapeshifter changes into a wolf, so instead of the prefix "lycan" or wolf, the delusion should really be referred to as therianthropy or zoanthropy or another term that better translates as "animal person." Old texts describe a wide array of possible transformations, including foxes, tigers, crocodiles, bears, great cats, elephants, sharks, or serpents, but wolf and dog seem to have been the most common in parts of the world where reliable records were kept.

We often imagine that ancient healers had a comically primitive view of illness. There are some valid reasons to hold that stereotype since you can open up a modern translation of the works of history's most famous ancient physicians and read stuff that seems, at least to our modern sensibilities, to be absolutely swirling fruitloops. It must be said, though, that the "sensibleness" of medicine has fluctuated over time. As near as we can tell, medieval texts genuinely do ascribe a large number of common maladies to demon possession or elf curses, and although we can't say for sure how much of this was felt to be metaphor at the time, they certainly seem earnest and sincere. When you really look into it, though, there seems to have been a sort of sine-wave pattern to the rationality of medicine. Whereas medieval texts really do seem to describe which abjurations will best protect the victim from Satan, ancient Greek texts clearly identify most cases of lycanthropy as a mental illness devoid of supernatural causes. A few years back, a Greek team published a summary of what ancient Byzantine medical texts as far back as the fourth century had to say about lycanthropy. The earliest surviving descriptions of the disorder hypothesize that it's actually a form of psychotic depression, and they describe the victims as confused, wandering, and "imitating wolves," but not, of course, unusually furry. In spite of the reasonably sensible understandings of lycanthropy, the treatments remained unsurprisingly ancient. The Byzantine texts describe "bloodletting until fainting" and treatment with theriaca, which was usually a potion made from an eclectic mixture of drugs that was used to treat snake venom. The most effective treatment while the person was acutely ill was to sedate them until they were calm, which, to be fair, is often the first step in modern care, too.

A review of the psychiatric literature published earlier this year looked at published descriptions of lycanthropy from 1850 to 2012 yielded about 56 recorded cases (baring in mind that the vast majority of cases of any illness don't get published), 15 where the transformation was to a wolf, 19 to a dog, 3 to a cat, two to a bird, and one each of bee, frog, gerbil, goose, horse, rhinoceros, snake, and wild boar. Some cases involved more than one animal. Not all of the papers specified the animal, which seems to me to be a heck of an omission from a good case description. The majority of these patients were eventually diagnosed with a major mental disorder to explain their delusion, primarily schizophrenia or some form of mood disorder, and as with all psychotic disorders, there was a much less than 100% cure rate.

It's finally interesting to note some of the causes of death described both in historical texts and in the recent review. The majority of individuals with lycanthropy go on to die of some ordinary medical problem, meaning that they live a life of unknown duration, but probably not excessively shortened... not counting those who had the misfortune to live during the time on the Inquisition. In more modern times, a small number of lycanthropy patients eventually died due to execution, often for murder or cannibalism, but a high number died of suicide and a small number actually died of starvation, because they believed they could eat only raw or rotten meat and they refused to do so. It goes to show that any mental disorder can cause suffering in more than just one way.

More than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on August 31, 2014. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.