Superiority in Numbers

What if having powers inherently encourages people to be heroic?

Dr. Eric Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC sourcebook, Insults & Injuries.

It’s often assumed that, given super powers, most people would misuse them, but what if having powers inherently encourages people to be heroic?

Most games are all about having special powers of one sort or another. In most superhero games, this is obvious; the characters are superhuman, even if “only” to the extent of a Batman, Comedian, or other “tourist.” Medieval fantasy isn’t always thought of in quite the same way, but when you really look at it, these games are still very much about playing superior beings, be it magically-empowered wizards or seemingly mortal fighters who none the less never tire, shrug off all pain, and charge fearlessly at horrific beasts. In each case, one of the essential elements of the story is that some people choose to use their powers for good, and others use them for ill. Many games make a not-unreasonable assumption: given special powers, a significant percentage of ordinary people will immediately use such powers to do evil. The exact size of this percentage seems to be variable. In most medieval fantasy settings, the vast majority of magically-powered individuals use their abilities for heroism, or at least, don’t use them to commit atrocities, such that heroes apparently outnumber the villains. In most superhero stories, it’s quite the opposite, and every hero is swamped by an entire rogues' gallery.

It's hard to know how true either of these would be. The cynics and misanthropes – myself included – argue that most people can’t even be counted on to drive ethically, let alone trusted with the ability to turn invisible or read minds. More optimistic or humanistic people tend to argue that, if superpowers were common, only a minority of people would commit actively vile and harmful acts, with the majority of people either being generally good-hearted or, at worst, neutral and boring and not being either outright heroic or villainous. We don’t know who’s right because this isn’t something we can really test; giving someone cheat codes in Grand Theft Auto and watching the inevitable carnage isn’t the same as turning someone loose in the real world where they can’t reload and erase the pain.

One funny thing, though, is that a handful of experiments have tried to look at this sort of thing, and evidence is surprisingly positive. While nobody has tested whether having powers will drive people to do right or wrong, it has been shown that people who use powers to do good things tend to continue to use their powers to do good things. For example, if people play a video game where they do good deeds, then they’re more likely to be nicer after they stop playing, while the opposite has sometimes, but not consistently, been shown for people playing games where they commit evil deeds.

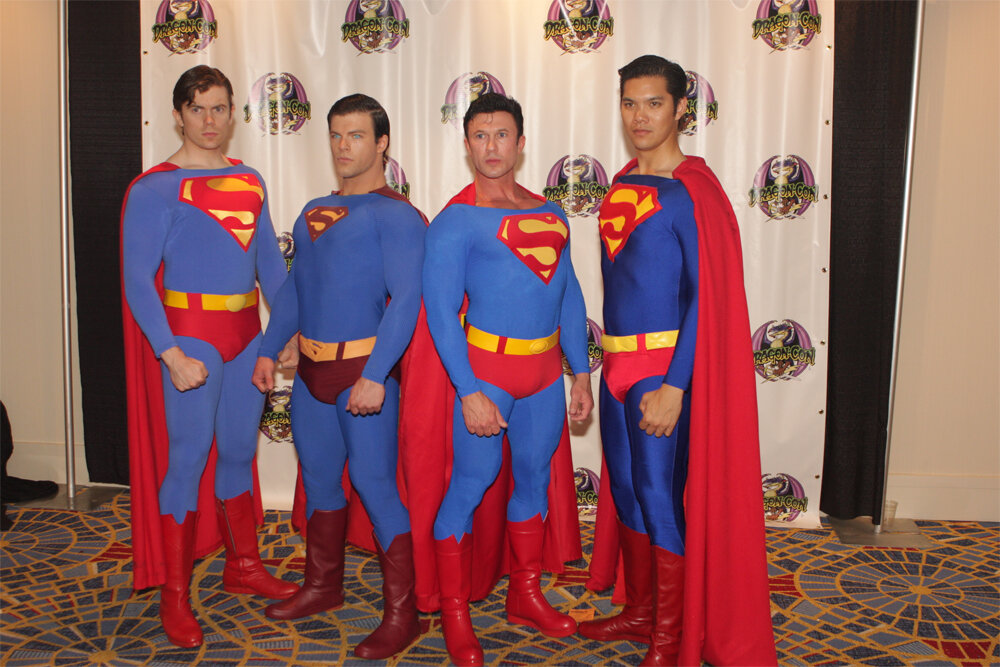

One study in particular gets at this question in an interesting way. Researchers put participants into a virtual reality game where they could fly around a city. The flight power was triggered by adopting the classic “up-up-and-away” Superman pose, which the experimenters theorized would intrinsically remind people of truth, justice, and the Western way. Participants were then randomly given one of two tasks: either fly around and explore the city, or locate a lost and sick child. As a control condition, other participants, instead of having the power to fly, were passengers in a virtual reality helicopter, and were assigned one of the same two tasks. Participants couldn’t help but find the lost child; it automatically spawned near the player after about three minutes, and there was therefore no option for the participant to be anything but the hero of the story. The real crux of the experiment didn’t come until after the VR helmet came off, however; on the way out of the room, the experimenter “accidentally” knocked over a container of pens, and assessed whether the subject helped pick them up, and after how long a delay. Participants who’d had the power to fly were quicker to help pick up pens, regardless of whether they’d been asked to save a child, whereas there was no difference in responses between people who had been touring the city versus searching for the child. So, something about being given a superpower had an impact on people doing a good deed afterwards, and actually performing a heroic action didn’t have an impact on a later good deed. The authors had a number of explanations for why rescuing the child didn’t have more of an impact, all of which boil down to the VR not being immersive enough, but in any case we can only guess.

There are a few reasons why this study might not say much about whether ordinary people developing powers would use them for good or ill. First, people here were not only given “powers,” but were then essentially forced to do a good deed with them. The experiment had the “non-heroic” condition of just exploring the city, but didn’t have an option for, say robbing a bank, or knocking a hero’s girlfriend off of a bridge, and we can only speculate what effect that would have had on subsequent pen-cleaning. Second, flight is a relatively non-abusable power; there’s only so much mischief a person can get into using just flight. Might the results have been different if the virtual reality game had involved a power which naturally lends itself to more villainy, such as invisibility, mind-control, or energy blasts?

It’s easy, and perhaps tempting, to imagine that the average person would misuse super powers. It’s actually difficult for me to imagine that simply having super powers might somehow inspire people to do good deeds, but as hard as it is for me to believe, part of me wants it to be true. Certainly, in our games, most of our superhuman characters serve the forces of good, or at least as Mal Reynolds might say, the all right. It could be that the average person is better than we sometimes think they are, and that superhumans might actually be better. Whatever the case, however many people prove to be better, they’ll still have their work cut out for them dealing with the people who don’t.