The Keys to the Leechdom

In the last few weeks' discussion of how healing was perceived in the ancient and medieval eras, I've focused on areas outside of the classical European historical periods. Today, we'll examine a bit about what's known from ancient Britain.

In the last few weeks' discussion of how healing was perceived in the ancient and medieval eras, I've focused on areas outside of the classical European historical periods which most influenced the best known fantasy settings. I've commented a few times on how European medicine was far behind that of other parts of the world, and this was a bit unfair of me. While the Arabs may have been far ahead of the Europeans in medicine for a good part of history, they by no means held the monopoly; the ancient peoples of Britain are known to have had a fair medical knowledge, but the chaos and warfare endemic to the region throughout the Dark Ages has meant that relatively little has survived to be studied today. Given that our games tend to draw more from Western European history than any other time period or part of the world, it would be a terrible injustice for me to completely ignore it, so today, we'll examine a bit about what's known from ancient Britain.

For those who want to do further reading, I'm drawing heavily from this article which was published a few years ago, but there are plenty of other sources out there once you have a basic idea what you're looking for. The article in question deals primarily with psychiatry as opposed to medicine as a whole, in part because this is the best paper I found and in part because I happen to be more interested in psychiatry than the rest of medicine. Seriously, though, a culture's perception of mental health, in so far as it's arguably the most ephemeral and indefinable aspect of healing, actually gives us a lot of insight into how the culture saw health as a whole. A society where healing was enmeshed in religion almost certainly had spiritual explanations for mental disorder, and a society that perceives mental health as biological is pretty much guaranteed to have had a biological explanation for the more "organic" diseases.

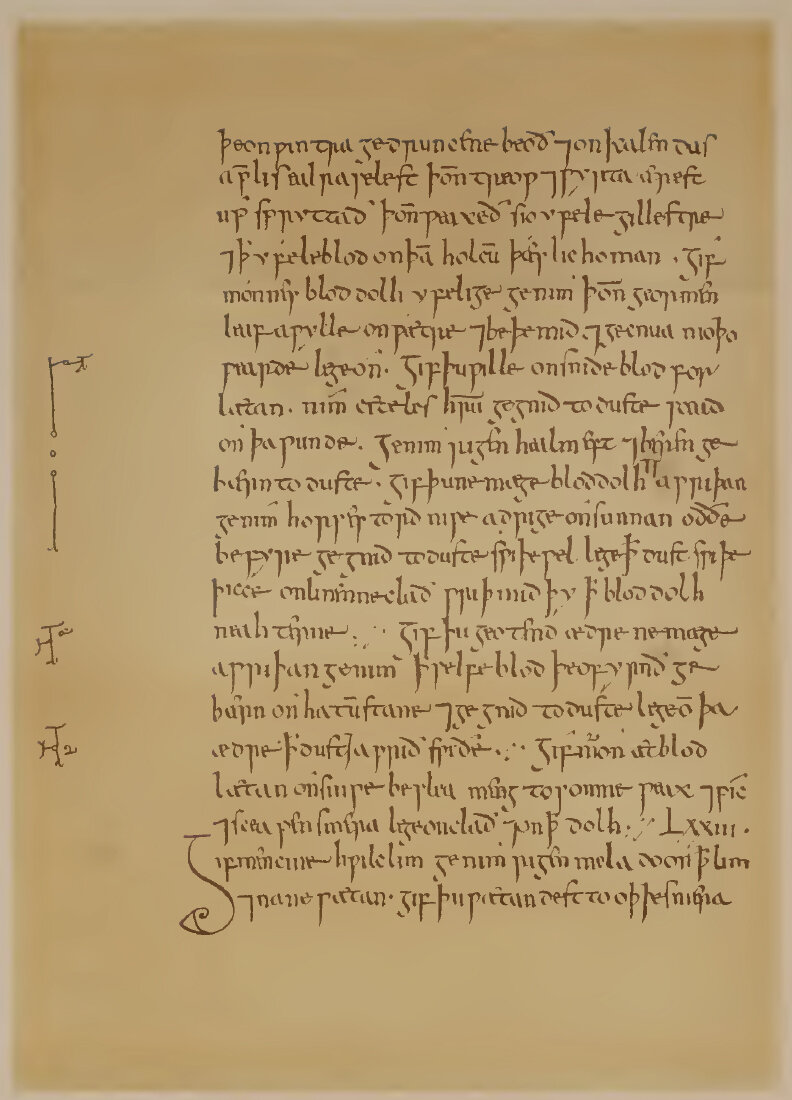

Amusingly, the best known surviving medical texts from ancient Britain are the Leechbooks. The doesn't refer to what you might think; leeches are not the mainstay of treatment described therein. Let's recall that the word "leech" didn't enter the English language as the name of an animal until about the twelfth century; prior to this, "leech" was a Germanic word that referred to the era's physicians and surgeons. The books feature a related word, "leechdoms," meaning treatments or cures. Another famous text is known as the Lacnunga, named for an Old English word for "remedies." As best as we know, these books date from before the dawn of the second millennium, but they're by no means the earliest records to survive, just the best preserved and most widely studied. The Leechbooks draw heavily from Greek and Roman writings, which is hardly surprising given that modern English texts continue to do so today. All the texts, particularly the Lacnunga, have a heavily spiritual bent; although they describe herbal remedies and relatively crude surgical procedures, many sickness are explicitly ascribed to being of demonic origin and prayer features prominently in many of the treatments. It's hard for us to know today how much of this almost mystical approach to healing really reflects the way healers thought back then and how much is simply the language they were using, complicated by our poor translations. On face value, at least, the texts appear to tell us that healers of the time blamed a lot of illnesses on magic and relied on magic to cure them.

How about mental disorder? Here, we run into the problem of description. Consider that in the past fifty years alone, psychiatry has completely changed the language which it uses to describe, and even conceptualize, mental disorder. If a field can change utterly in fifty years, imagine how different conceptualizations must have been a thousand years ago. The Leechbooks describe people who seem to be suffering from conditions that we might today identify as schizophrenia and dementia, but also describe conditions which we haven't been able to puzzle out. The "chapters" on mental health include such entries as devil sickness and elfin tricks; it's not a huge leap to imagine that these might have been people who heard voices saying disturbing things that no one else could hear. All together, the books strongly suggest that the healers of the age saw mental illness as being distinct from physical illness, since they weren't in the same chapters as diseases of the head, but also that mental disorders may have been deemed to have come from demons and fae as opposed to problems of the body itself.

As far as treatment goes, the books relief heavily on seemingly magical cures -- everything from prayers to blessed amulets to tying parchment inscribed with holy words around the neck -- , but also on physical remedies. The article cites an example of a potion to cure fiend sickness, made from lupin, bishopwort, henbane and cropleek ground together, mixed with ale, left to stand overnight, and then diluted with holy water. We see two interesting things here. First, it illustrates that even when a physical medicine is being prepared, holy water was still added, just for good measure. Second, we see actual psychoactive plants in the recipe. Henbane is a hallucinogen for humans and causes restlessness and dilation of the pupils, while bishopwort is used in modern herbalism as an anti-anxiety drug (with very limited scientific basis, mind you). This particular blend could perhaps have been a potion to treat depression, by improving mood and boosting energy, and then again, perhaps it was just a mix of plants with no basis other than wishful thinking. Even the most pragmatic-seeming potion recipes often included some ritualistic element, such as gathering the herbs at a certain hour or drinking the mixture out of a church bell. Interestingly, healers using these texts would almost have to be priests themselves, since the healer had to be able to recite a number of different prayers, masses, and psalms. Did any of it actually work? The paper's author speculates that the placebo effect may have been the most powerful element of many of these cures, but since many of the plants involved do have potential medicinal (or more commonly, poisonous) properties, such as nightshade or St. John's wort, it's entirely possible that the Leechbooks contain some genuinely effective pharmacology.

Since the article I'm, drawing from isn't freely-accessible without institutional access, here's a selection of some of the illness names in both Old English and modern English. In addition to giving you a flavour for how tenth-century healers understood sickness, you can have fun sprinkling these terms into your games and seeing where that takes you.

| Ungemynde |

Dementia |

| Deoful fede |

Devil possessed |

| Fordrince |

Drunkenness |

| Ælfadl |

Elf disease |

| Ælfsogoþa |

Elf hiccough |

| Ælfsidenne |

Elvish influence |

| Ælfsidene |

Elvish tricks |

| Yfelre leodrunan |

Evil sorcery |

| Feond seocum |

Fiend sick |

| Mnoðes hefignesse |

Heaviness of mind |

| Dyrgunge |

Idiocy |

| Micel wæce |

Insomnia |

| Unlust sie getenge |

Loss of appetite |

| Wræne |

Lustful |

| Weden heorte |

Mad heart |

| Nihtgengan |

Night goblins |

| Deofler costunga |

Temptation of the Devil |

| Feondes costungum |

Temptation of the Devil |

| Unwræne |

Un-lustful |

| Gewitseocne |

Wit sick |

| Þam mannum þe deofol mid hæmð |

Women with whom the devil has intercourse |

More than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on February 01, 2014. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.