Nine-Tenths of Sanity

There are places and situations where it's more socially appropriate to be crazy than others.

I use the word "crazy" above with my tongue firmly in cheek, for the record. One of my deeply-held beliefs is that despite near on ten years working in the mental health field in one capacity or another, including more than six months training on an acute inpatient psychiatry ward at a major general hospital, I don't think I've ever seen a crazy person. Sure, I frequently see people who hear voices that nobody else can hear, and sometimes they believe that these voices are being beamed into their head by shadowy government organizations. A few times a year I meet someone who's convinced that their family members have been replaced by imposters, or that they're the messiah, or people so psychotic that they're incapable of forming a complete sentence, but while I've seen a lot of very sick people in my career, I honestly can't say that I've seen anybody crazy. It's easy to spot someone who's behaving crazy, but notwithstanding the seven letters of acronyms that come after my name on my business card, I can't imagine what someone who actually IS crazy would look like.

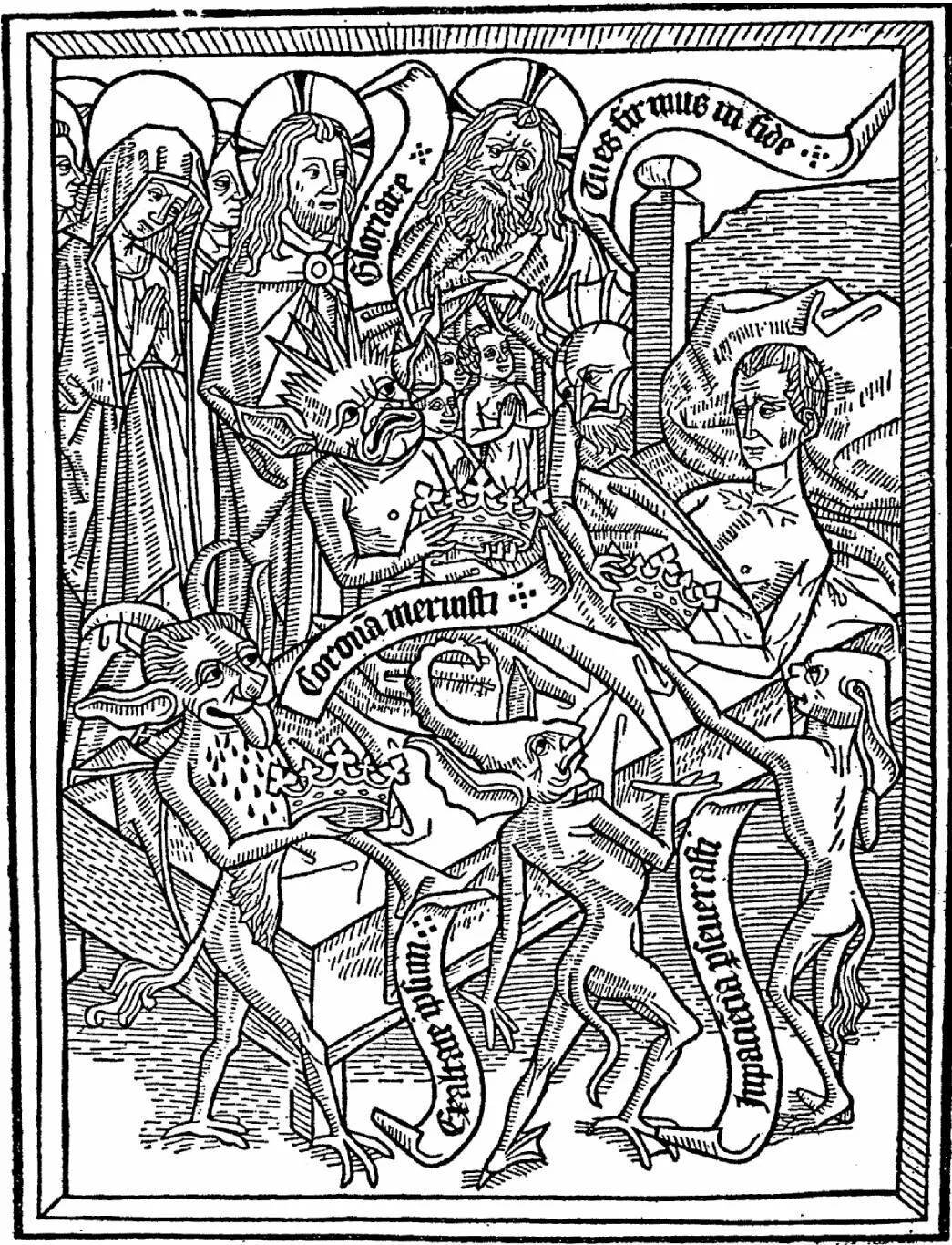

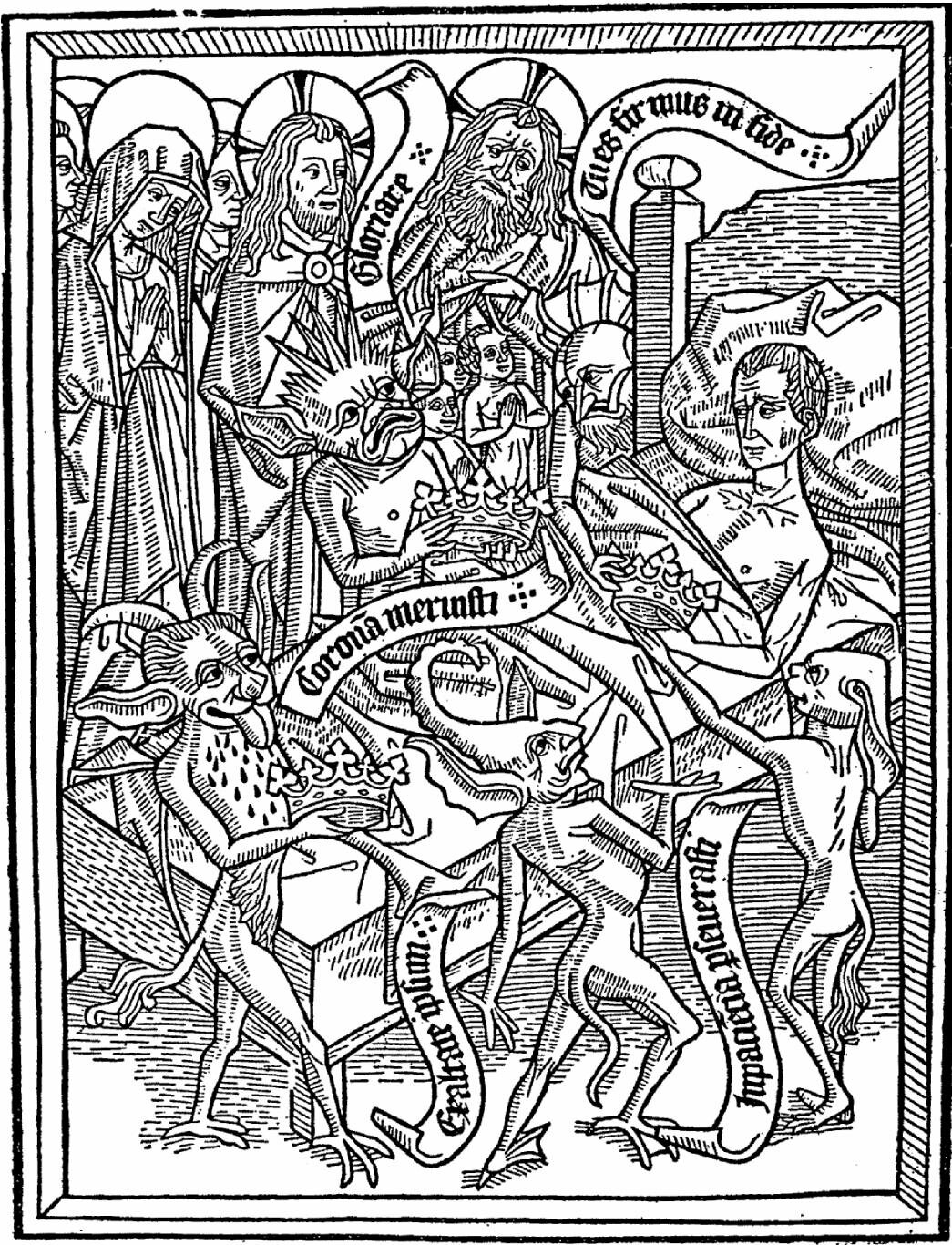

One of the fun parts of my job is that I get to work with medical students. Medical students are entertaining because they're generally hard-working, keen, earnest, and full of questions, and it boosts my ego to be able to answer their questions. When I ask what the students if there's anything specific that they have questions about, a good half of them answer this: they're unsure how to distinguish clearly delusional ideas from the merely weird ones. In the emergency room, a physician or other mental health worker likely has an hour or less to sit down with someone they've never met before, get their whole life story, uncover any odd beliefs they may have, and decide if those ideas are so odd as to merit hospitalization and/or medication. In a major metropolitan city, people with weird ideas pass through the emergency department, and depending on one's personal threshold of "weird," to say nothing of one's cultural background, determine whether it's weird enough to scare you. If you had never heard of Christianity, then a priest telling you about Jesus would sound psychotic, so when you sit down across from someone who's afraid that their son is possessed by a demon, it can be hard to decide whether they're sick, or just come from a different cultural group than you.

On a related note, I've always wondered what would happen if you took a group of priests, rabbis and imams and gave them an adequate trial of an antipsychotic medication. Probably it would have no effect at all except to make them more sleepy, but to my knowledge nobody's ever actually done the experiment (getting the ethics approval for that one would be an adventure), so we don't know for sure.

Compare two cases of "demon possession" that I evaluated some years ago, within six months of each other.

The first case was a family of refugees from an African nation. The mother was a bit younger than me, and had a pre-school aged son who she believed was possessed (more precisely, she believed he was an "enfant sorcier," but close enough). She had ample evidence for this, mostly from various dreams that she and her husband had experienced. When I met the boy, he was a quiet, bright, well-behaved child who was obviously terrified of his mother. When he was seen without her in the room, he was playful, generous, and perfectly appropriate... better behaved than most Western kids, in fact. On digging into the story, the mother was herself a survivor of terrible abuse at the hands of government soldiers and torturers back home, and her son represented to her all of the horror she had lived through. She wasn't psychotic, though, and the boy certainly wasn't possessed; in the culture where she had grown up, immersed in traditional religion and where magic and curses were a fact of life as opposed to a part of mythology, it was entirely appropriate for her to believe as she did. Not good, of course (and in the end, the child had to be taken away by youth protection, at the mother's insistence, because he would otherwise have been killed), but culturally-appropriate.

The second case was a middle-aged Inuit woman, admitted to a general surgery team for treatment of an intestinal problem. The surgeons asked for a psychiatric evaluation when she rather sheepishly admitted that she was possessed by the devil, and wanted them to bring in a priest to exorcise her. When I met her, she freely admitted that she (and only she) could hear the voice of the devil, which was telling her to kill herself. She had no other symptoms and was otherwise quite logical and well-spoken; this is important because a chronic psychotic disorder, like schizophrenia, wouldn't have just one single symptom. On further questioning, I found that she'd previously been a heavy alcohol user (her daily intake would be enough to kill a novice drinker like me) and hadn't touched a drop in about a week. Diagnosis: psychosis caused by alcohol withdrawal. An important piece of information was that she was Inuit, who had grown up a non-practicing Christian; unlike a woman raised in the traditional faiths of Africa, it was totally out of the ordinary for her cultural background to believe that she was possessed.

The Inuit woman was prescribed medication, and the African one wasn't. Sadly, but for much the same reasons, the Inuit woman's belief that she was possessed went away, and the African one's belief that her son was possessed didn't.

Both of these women had the potential to look crazy. In my opinion, neither one actually was. I'm not sure that explaining it like this to my students actually makes the question any clearer to them, but they all nod and pretend that they understand.

More than four years ago, Dr. Eris Lis, M.D., began writing a series of brilliant and informative posts on RPGs through the eyes of a medical professional, and this is the one that appeared here on October 20, 2013. Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC OGL sourcebook Insults & Injuries, which is also available for the Pathfinder RPG system.