Love Bites

Lycanthropy doesn't follow the classic patterns that we associate with real-world diseases, but we can perhaps infer whether it can be sexually transmitted.

Dr. Eric Lis is a physician, gamer, and author of the Skirmisher Publishing LLC sourcebook, Insults & Injuries.

It says a lot about geek culture that I'm far from the first person to ever ask if lycanthropy is can be a sexually-transmitted infection.

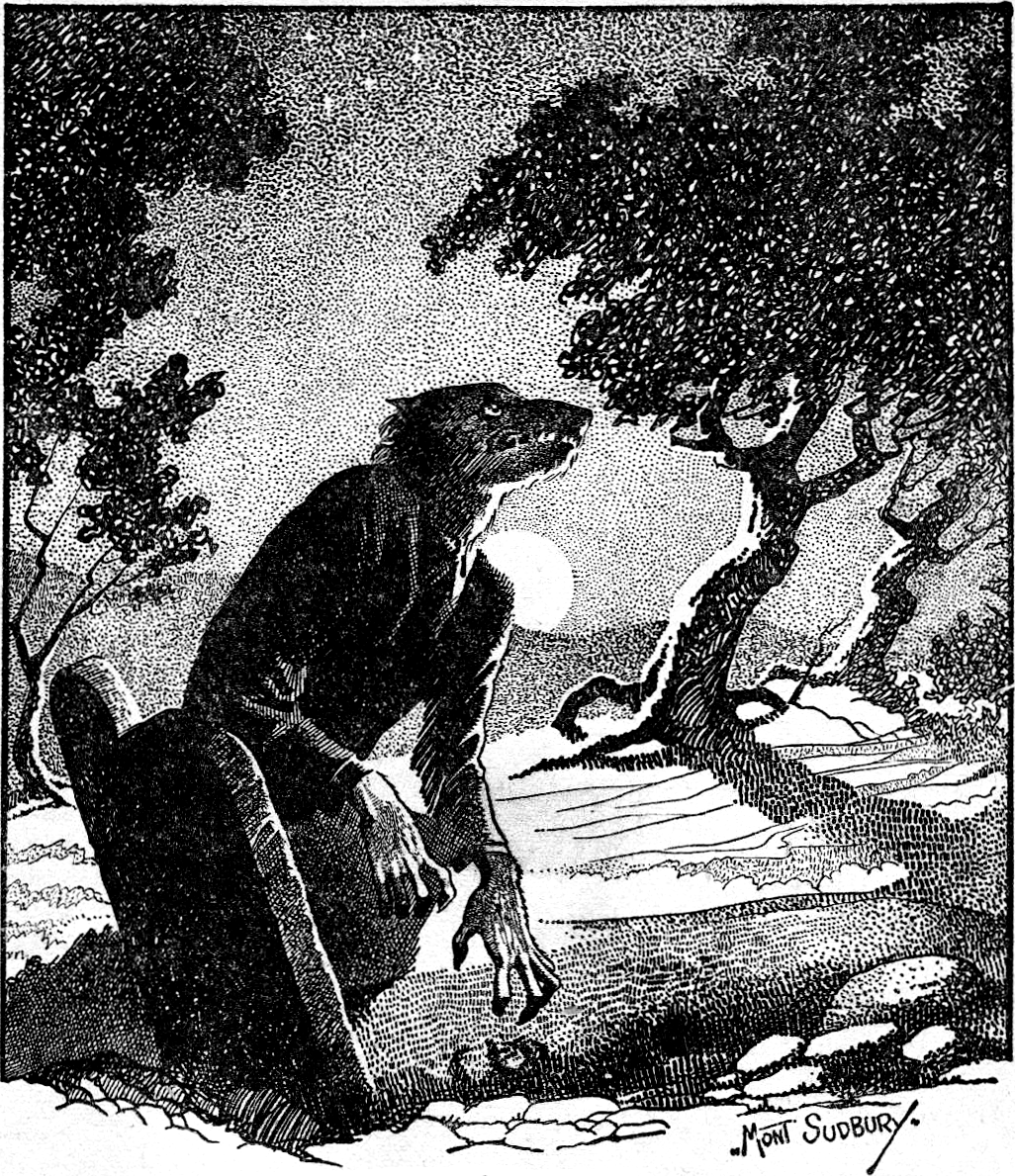

Lycanthropy, in our games at least, occupies an interesting role on the border of sickness and curse. In the two most popular SRDs, it's explicitly described as an infection, but it can be cured through spells that stop diseases as well as by spells that stop curses, in addition to being cured, in some circumstances, by herbalism. Not surprisingly, lycanthropy doesn't follow the classic patterns that we would associate with a real-world bacterial, viral, fungal, or prionic infection, so it's hard to speculate as to precisely what sort of infection it might be without resorting to the old cop out of, "it's magic." We can, however, infer a certain amount of the biology and pathophysiology of lycanthropy by examining how it's spread, and specifically, whether it can be sexually transmitted. We can't necessarily come up with any answers, but we can at least point out some entertaining questions, which is often what science is all about.

As an amusing aside, the D&D SRD states that lycanthropy can be treated with belladonna, whereas the Pathfinder SRD states it can be cured with wolfsbane (which are not the same plant, contrary to the D&D SRD). Given their effects on the body, neither of these plants should really be called an antibiotic or antiviral. It would actually be most accurate to say that lycanthropy is treated with chemotherapy.

Let's take a second to think about how sexually-transmitted infections work. Broadly speaking, an STI is an infectious pathogen with an unusually poor capacity to survive hostile environments. Most pathogens that infect the human body thrive in warm, moist, nutrient-rich environments, which describes most of the body. Most infections bacteria are good at surviving outside of these ideal environments, from the relatively delicate Salmonella and E. Coli that can survive a few hours, to bugs like C. difficile that can form a durable spore and survive for months. Anthrax and smallpox, under the right circumstances, can persist for years. Viruses aren't much different; most of the viruses that cause the common cold can survive anywhere from a few hours to a couple of days on a doorknob or computer keyboard. In contrast, the bugs that cause STIs tend to have exceptionally short lives outside of the body. HIV, possibly one of the most feared infectious agents in human history, is thought to have a lifespan of mere minutes in a dry environment... hence the ridiculousness of some of the old urban legends about contaminated needles being left in movie theaters and such. Similarly, the agents that cause herpes, syphilis and gonorrhea are extremely short-lived unless kept at just the right temperature and adequately moist. Human papilloma virus, which causes warts, is an exception to the rule, but we'll ignore it for today since it operates differently from other STIs in all sorts of other ways that make it less relevant to this discussion. The important thing is that, by and large, any infection that's primarily spread via blood contact does so because it's not durable enough to spread in any other way.

Consider HIV as a "prototypical" blood-borne infection. The virus can pretty much only spread from fairly direct blood-to-blood contact. A shared syringe can transmit the infection because of blood stored within the hollow needle, and a blood transfusion can pass on the virus pretty directly. In the case of sexual transmission, the virus passes through microscopic tears and abrasions in the skin that result from, shall we say, prolonged friction. Women are at greater risk of contracting the virus than men because keratinized skin is more durable than the epithelial lining of the reproductive tract, and anything that involves existing wounds or more easily torn tissues further increases the risk. You can read about the actual risks of transmission from different sex acts here, but by and large, the risks of a single interaction are very, very low. Importantly for our discussion today, HIV is barely present in the saliva; even a skin-breaking bite from an infected individual is thought to be "epidemiologically insignificant." The same is true for most other STIs; assuming there are no active, open wounds around the mouth of the attacker, the odds of transmitting an STI by saliva or bite is very low. It goes without saying that the odds of transmission by fingernails is even lower; you're at real risk of getting skin and wound infections from a human's "claw attack," but not so much HIV.

This brings us to lycanthropy. Depending on which rules you read, lycanthropy is spread when a werebeast causes significant wounds to another creature. In Pathfinder, the wounded creature has to make a Fortitude save against a base DC of 15, which arguably puts it in the average range of infectivity compared to other diseases in their SRD. In the old Ravenloft books, there was a more elegant mechanic; depending on which sourcebook you read, there was a 1% chance of infection per point of HP damage dealt either by an attack or over the combat. Pretty much every sourcebook agrees that the werebeast can infect via a bite or a claw attack and, obviously, not with a dagger or something. What all of this tells us is that lycanthropy looks very much like an STI in some respects, in that it depends on a fairly intimate contact with the blood, but very much unlike an STI in some others. There might be a few explanations here, of course; it could be that a werewolf's teeth and claws make contact with its infectious blood when they sprout, leaving them infectious for two to three minutes, or perhaps it's assumed that the werewolf's gums and fingertips get cut when they hit a foe's armour, allowing blood to spatter. Then again, maybe it's just a biological implausibility meant to make the enemy scarier.

So, should lycanthropy be sexually transmittable? It seems likely, although the risk is presumably low. Although sex does cause tiny wounds and allow some sharing of blood and fluids, most people don't take hit point damage from it (depending, obviously, on what you're into). If the disease is only transmitted only by hit point damage, and especially if you use a risk of infectivity that scales with damage dealt, then the risk from a non-violent sex act is probably less than one in a thousand (possibly closer to one in five hundred for the female or one in a hundred for a receiving male), and that's taking into account that lycanthropy seems to be quite a bit more infectious than HIV. The risk should certainly be miniscule compared to the risks of contracting it in battle.

Then again, one in a thousand chances come up in pretty much every gaming session, and the storyteller shouldn't necessarily shy away from a potentially amusing story hook, assuming the players won't be upset by sensitive matter.